Electrifying the two-wheeler

Alta Motors did not set out to create a zero-emission vehicle or invent a vital cog in the new landscape of electrified mobility. It wanted to build the best motorcycle it could regardless of powertrain, with products to satisfy the most serious motorcyclists. The fact that Alta’s electrified two-wheelers are pushing the envelope in terms of power density and control algorithms is secondary, as the company seems mostly fueled by a genuine passion for its products.

They’ll need that zeal, because they’ve entered a rough market, irrespective of propulsion source (see “Making It…” sidebar). Alta also has taken more of a racing-focused and proprietary component route, accepting fewer compromises from a supply base that is still struggling with automotivescale electrified products, never mind those of a motorcycle startup.

This is a tougher route to ride, and such tenacity may bring more pains as the company grows, but it’s quickly won Alta’s products many fans in a niche field. Automotive Engineering spent a day with company co-founder and CTO Derek Dorresteyn discussing Alta’s genesis, technology and products. Our visit also included ripping up the nearby streets of San Francisco on several Alta offerings to see if the hype around one of the newest OEMs was warranted.

Competition-focused product line Alta does not build touring bikes. It instead applies research and engineering resources towards motorcycle products that best leverage the strengths of an electric powertrain (instant torque) and minimize the drawbacks (range). The result is Alta’s lineup of competition-grade off-road motocross, street-legal enduro/dual-sport and street-legal supermoto models.

The week we visited, Alta earned its first AMA Pro EnduroCross podium, competing on equal footing with gasoline powered machines. A tour of Alta’s corporate offices and manufacturing line in Brisbane, Calif.—housed under one roof in a nondescript industrial park just south of San Francisco —was led by Dorresteyn, who along with Jeff Sand (chief design officer) and Marc Fenigstein (chief product officer), founded Alta in 2010 and moved Alta to the Brisbane location in 2015.

“Jeff Sand and I had gotten together over the idea of an electric motorcycle and we were working on it nights and weekends. That was 2008 and ‘09, and in 2009, we also brought on the third co-founder, Mark Fenigstein,” Dorresteyn explained. “At the time, I owned a CNC machine shop in San Francisco and ended up staffing out a little bit, hiring additional engineers to work on this and we got to a concept point where we thought it was worth trying to form a company and raise some capital.”

The nascent OEM quickly outgrew the machine shop, noted Dorresteyn, a fourth-generation Californian who studied industrial design at San Francisco State University. The team proceeded to build out the Brisbane space from an empty shell in 2015, and by the time of our tour in 2018, were already looking for additional facility space.

Dorresteyn impresses as sort of a Conan O’Brien/Tony Stark mashup, providing the sense that if ever held captive in a cave by terrorists and you had him, a welder and a lathe, you’d likely Iron Man your way out. This comes to mind as we’re walking the low-key production line laced with networked Raspberry Pi modules tracking assembly metrics.

Dorresteyn is calmly explaining that thanks to the battery pack’s IP67 waterproof rating and automotive-grade connectors, theoretically, you could ride an Alta motorcycle underwater. “Not that I can recommend it,” he said, while also noting the pressure-relief capability for high-altitude riding. Low volume derived from high volume That Alta-engineered, -designed and -built 5.8-kW·h Li-Ion 350v battery pack is the heart of its products. Currently on what Dorresteyn claims is “version 1.5,” the 67.9-lb (30.8-kg) pack uses the same cylindrical 18650 cells that Tesla has applied, a keen counter to low volumes.

“This is something that Tesla founder Martin Eberhard realized some years ago, that cylindrical cells are currently produced in the highest volume of any format of lithium-ion batteries,” Dorresteyn said. “Because the volume is there, we’ve got very high quality, the latest technology and because it’s a standardized format, we have some amount of competition between different manufacturers.

All that adds up to a better business case and a better product case.” Alta’s battery technology is focused on the integration of cylindrical cells and is easily extensible into the 21700 or other cylindrical formats, Dorresteyn explained. “We’ve worked hard to develop relationships with some of the biggest and best battery technology companies in the world,” he said. “That was a heavy lift, because we had to convince these companies that we could safely integrate their technology into a high-voltage automotive battery pack.”

Power density with safety Alta claims one of the industry’s highest system-level power densities at 185 watt-hours per kilogram. “A lot of the work we’ve done is how do you take mass, cost and volume out of the system and still safely integrate a high-voltage pack to the cell?” Dorresteyn asked. “We’ve developed the full stack of the EV drivetrain from cell-to-output and everything in between—all the electronics, all the firmware—and we think it’s absolutely critical to producing class-leading products.”

The approach has allowed Alta’s engineers to work quickly to improve and advance these systems, but also not to be beholden to other partners’ concepts or priorities. They’ve also focused great attention on propagation resistance, an aspect of battery-pack design that Dorresteyn believes does not receive as much as attention as it should.

“If you have a battery cell that, for a myriad of reasons—it could be a manufacturing defect, a mechanical intrusion—goes into thermal runaway, that heat doesn’t bring other cells in the pack also into thermal runaway,” he asserted. “This is one of the foundations of our safety approach to lithium-ion batteries and we’ve developed patents around that.”

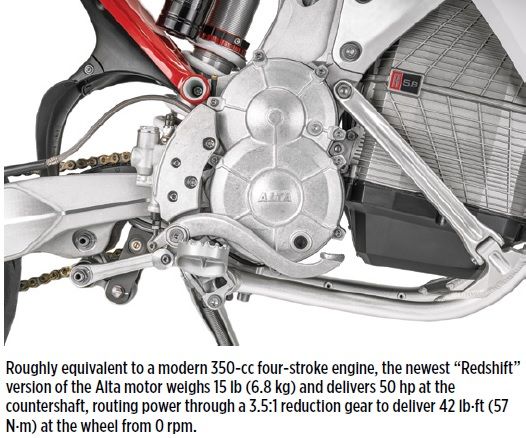

Past the power source Alta assembles its components into complete motorcycles via a snaking, on-site assembly line, with the battery pack powering a 14,000-rpm permanent-magnet AC motor located at the motorcycle’s roll center. The placement and low counter-rotational mass permits what Alta claims is “the lowest polar moment of inertia in motorcycling” to reduce gyroscopic effects on handling.

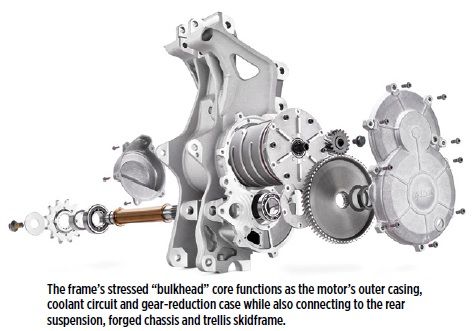

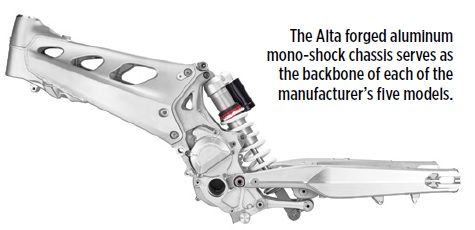

Roughly equivalent to a modern 350-cc engine, the newest “Redshift” version of the motor weighs 15 lb (6.8 kg) and delivers 50 hp at the countershaft, routing power through a 3.5:1 reduction gear to deliver 42 lb·ft (57 N·m) at the wheel from 0 rpm. The frame’s stressed chassis core (what Alta labels the “bulkhead”) functions as the motor’s outer casing and a coolant circuit for the liquid-cooled motor and inverter, as well as the transmission case for the gear reduction. It’s also the main structural hub connecting to the rear suspension, the forged chassis and the trellis skidframe.

Aside from the electrified powertrain, the bodywork, suspension, brakes, wheels and tires on all Alta models are entirely conventional, and therefore compatible with a host of aftermarket suppliers. On the road Alta’s motorcycles, particularly the latest Redshift models that added power and range, have received overwhelmingly positive reviews. After chasing ex-prolevel motocrosser Dorresteyn around the wildly entertaining San Francisco streets on dual-sport and supermoto models, AE believes the praise is warranted.

The seamlessness and intuitive linearity of the controls belie Alta’s limited time in the industry. “One of the things that’s different from the car world is that you use wheel slip as a control vector, especially in off-road motorcycles,” Dorresteyn explained. “And there’s an expectation by the rider for that to happen in a very intuitive way, so they feel confident in the way the machine is behaving. We’ve done a tremendous amount of development and testing around those characteristics.”

That work paid dividends, as Alta’s products are serious motorcycles that welcome aggressive riding and easily live up to the performance expectations of seasoned pilots. The biggest adjustment from a conventional motorcycle is about all the things you don’t have to do (warm up the engine, shift gears, clutch, etc.), leaving a safer chunk of attention for piloting duties. A ride selector with four distinct modes provides a machine with personalities from docile to hooligan, making it simultaneously suitable for novice or expert, or a machine to grow with.

The other big adjustment is an e-moto’s lack of noise. Silent save wind noise and chain whir, the rider feels almost unnaturally aware and plugged into the surroundings. “The lack of noise is a huge benefit across the entire spectrum of motorcycling,” Dorresteyn said. “When you look at the loss of riding areas in the world, the move out of the urban areas, the loss of race tracks, it’s almost 100% driven by noise compliance.”

Engineering in the e-mobility space So how does Alta view itself in a rapidly shifting mobility landscape? “We’re currently a motorcycle manufacturer, but we’re also an electric drivetrain developer and manufacturer,” Dorresteyn explained. “In the process of building an electric motorcycle, we’ve built a deep team and level of expertise around all the components of an electric drivetrain.”

That expertise is not always easy to come by. Dorresteyn noted that much like aerospace did in L.A. starting in the late 1950s, the e-mobility craze in the Bay Area is a double-edged sword: There’s talent available but you’ll pay for it. On its 40-strong engineering staff, Alta counts a number of ex-Tesla employees, plus Formula SAE alumni. “We have industrial design, mechanical, electrical, firmware, software and test engineers and some specialists in things like thermal and simulation. We also have, separate from all of that, manufacturing engineering, which is constantly trying to increase our quality by improving traceability and control of everything we manufacture.”

Challenges and the last mile Particularly for racing and off-road applications, riding range may not be the non-starter for motorcyclists it is for consumers in the automotive space. “It’s still a hurdle for us, but we’re trying to select markets and segments of markets that satisfies most consumers’ use cases,” Dorresteyn admitted. “We’re focusing on urban transportation and off-road, where the total energy required is less.”

As far as being part of the larger electrified landscape, unlike e-bicycles and scooters, Dorresteyn says he would not position e-motos and Alta in the same “last-mile” scenarios as those lower-speed solutions.“When we think of last mile now, we think of literally going a mile or two at relatively low speeds with a conveniently placed public transportation vehicle that you can pick off a rack and ride to work and ride back. “Motorcycles are personal transportation and they’re a lot of things that scooters and e-bicycles aren’t,” he opined. “They’re exciting, quick, very capable. You can crisscross a city. It’s a much more personalized form of transportation and also expressive of the owner and rider, something they take as part of their image to the world.”

As for being part of the larger-scale e-mobility landscape, Dorresteyn says Alta is all in, and few who have experienced it would argue when he says: “The supermoto-bike that we have, in an urban environment… I have not ridden anything that is more fun than that.” “Passion is a pretty important thing for us,” Dorresteyn said. “We have people that are passionate for building better motorcycles, and for building better EVs. We have people that are passionate about the electrification of transportation as a whole and about their specialties in design engineering. That’s what drives this place, completely.”

Making it in e-motorcycles

Motorcycle sales in the U.S. have not rebounded since the Great Recession, hovering around the 500,000 units/year-mark since 2009, when the recession more than halved sales. Global markets—where motorcycles purchases are less discretionary and smaller displacement machines often dominate the urban landscape—have rebounded far better since the recession, while the U.S. has seen additional casualties.

The U.S. motorcycle market has been a rough business since its inception. After its founding in 1903, Harley-Davidson (H-D) outlasted dozens of competitors to become the sole volume American manufacturer for decades. Polaris Industries launched Victory Motorcycles in 1998, and though it ended the brand in 2017, it continues in-essence as Indian Motorcycle. For electrified drivetrains, none of the global motorcycle OEMs have yet to commit, save KTM with a single off-road model, the Freeride E-XC. The Lightning brand has demonstrated stunning performances at places like Pikes Peak and Bonneville with its LS-218 superbike, but seems to be in perpetual prototyping mode since launching in 2006.

Mission Motors (which was involved in H-D’s LiveWire project—see sidebar) ceased operation in 2015, the same year Polaris Industries acquired Brammo’s e-moto division which it then nixed in 2017 along with the Victory brand under which it was marketed.This e-moto pair join gasoline-powered makes Motus and Buell in the recent “former” column of motorcycle manufacturers.

On the electrified front—with Alta Motors recently going into a non-producing “low-power” mode at presstime, presumably in hopes of securing new financing—the current major domestic player is Zero Motorcycles. Another NorCal operation begun as Electricross in 2006, Zero now builds 2,000 bikes a year in Scotts Valley just north of Santa Cruz. It is the only manufacturer to provide a full-range electric motorcycle via its 13 kWh Zero S model (shown at left), claiming a 223-mile (359-km) urban capability.

Zero offers six street and soft-roading models, with export distribution in Europe and Australia. Italy’s Energica Motor Company, a Modena-based subsidiary of CRP Group, builds three trellis-framed electric sportbike models (Eva, Ego and EsseEsse9) around an 11.7kW·h lithium-polymer battery pack and oil-cooled, permanent-magnet motor. Featuring four riding modes with four regenerative maps, depending on the model, Energica’s powertrain delivers 148 lb·ft (201 N·m), 145 hp and a 150-mph (241-km/h) top speed.

Harley-Davidson amps up (literally)

In July 2018, American motorcycle maker Harley-Davidson made a nearly unprecedented announcement about its future products. Part of a global investment strategy to help create a new generation of motorcyclists, the plans from H-D promised not only a novel and global mix of products in new segments (including adventure, street-fighter and small-displacement machines), but also a commitment to electrified motorcycles.

This includes the 2019 launch of its stunning LiveWire (which first debuted in conceptform in 2014; bottom photo), followed by two new middleweight e-models with “accessible power and price points,” and three new lightweight (think urban, scooter or e-bicycle-like) models by 2022.

Then in September, H-D announced it is establishing an R&D center in Silicon Valley to help engineer this new electrified lineup, with the facility serving as a satellite of itsMilwaukee-area product development center in Wauwatosa, Wisc. H-D claimed it planned to hire 25 people from the Bay Area with electrical, mechanical and software engineering skills and will open the new center in the fourth quarter of 2018.

H-D remains mum about its previous equity investment in Alta Motors—which in mid-October reportedly ceased production of Alta-brand electric motorcycles—and the work it had done with the now-defunct Mission Motors on the LiveWire concept. But with its July announcement and creation of the Silicon Valley center, H-D apparently has committed to its own e-moto engineering.

This new facility will serve as a satellite for the Willie C. Davidson Product Development center in Wauwatosa, which is where I’m located,” explained Sean Stanley, H-D’s chief engineer for EV platforms. “It will initially focus on EV research and development and it includes battery power electronics, emachine design, development and advanced manufacturing.

“I will be working directly with the EVsystems team there, establishing an EV architecture and building blocks that can support many of the vehicles that we plan to bring to market,” Stanley told AE. “At the PDC in Wauwatosa, we’ll take those building blocks —that the Silicon Valley center develops— through the product development cycle to prepare for commercially available vehicles.” So far, H-D is the only major motorcycle OEM to announce specific plans for an electrified addition to its traditional lineup. Next year’s LiveWire is being positioned as a “premium, highperformance motorcycle with streetfighter style and attitude.”

As to what’s prompted the first major OEM—one legendary for its V-twin engine architecture and characteristic exhaust note—to add electric offerings, Stanley noted that, “EV technology has a lot to offer in the area of new experiences and connections to the motorcycle and environment around you. Simplistic, twist and go riding [as] there’s no shifting. Reducing the noise to focus more on the experience of riding. The instant torque, reduced maintenance. A bike that’s easy to control for novice riders, all the way up to performance that intrigues experienced riders.”

And what about that sound? “A Harley-Davidson wouldn’t be a Harley without a signature sound,” Stanley said. “We have and will continue to focus efforts in this area and deliver an authentic and unique sound.”

Written by: Paul Seredynski

Source: Automotive Engineering

Automotive Engineering magazine is the No. 1 resource for engineers across multiple disciplines in the automotive industry. Published 10 times annually, Automotive Engineering engages decision makers who buy and specify product. Each issue includes special features and technology reports, from topics such as: vehicle development and systems engineering, powertrain and subsystems, environment, electronics, testing and simulation, and design for manufacturing.