The class develops the second life of electric vehicle batteries as energy storage at Rome-Fiumicino Leonardo da Vinci Airport and the implications for fleet management.

Slide 2. The case of Rome-Fiumicino Leonardo da Vinci Airport.

- The second life of electric vehicle batteries.

Second-life batteries are those that have reached the end of their automotive life but whose residual performance remains at 70-80% of their total usable capacity. This means they can be used in stationary applications, in combination with renewable energy generation systems such as solar and wind, and/or to provide services to the electricity grid. Extending the useful life of batteries means reducing their carbon footprint and increasing the amount of renewable energy in the grid.

By having an intermediate step, or a ‘second life’, between their use in electric mobility and their recycling, costs are optimized throughout the supply chain and electric cars become cheaper. Last but not least, it is a sustainable option in three ways: good for the environment, the company, and society.

Giving electric car batteries a second life is essential, not only to limit waste but also to reduce the consumption of their raw materials, which are finite.

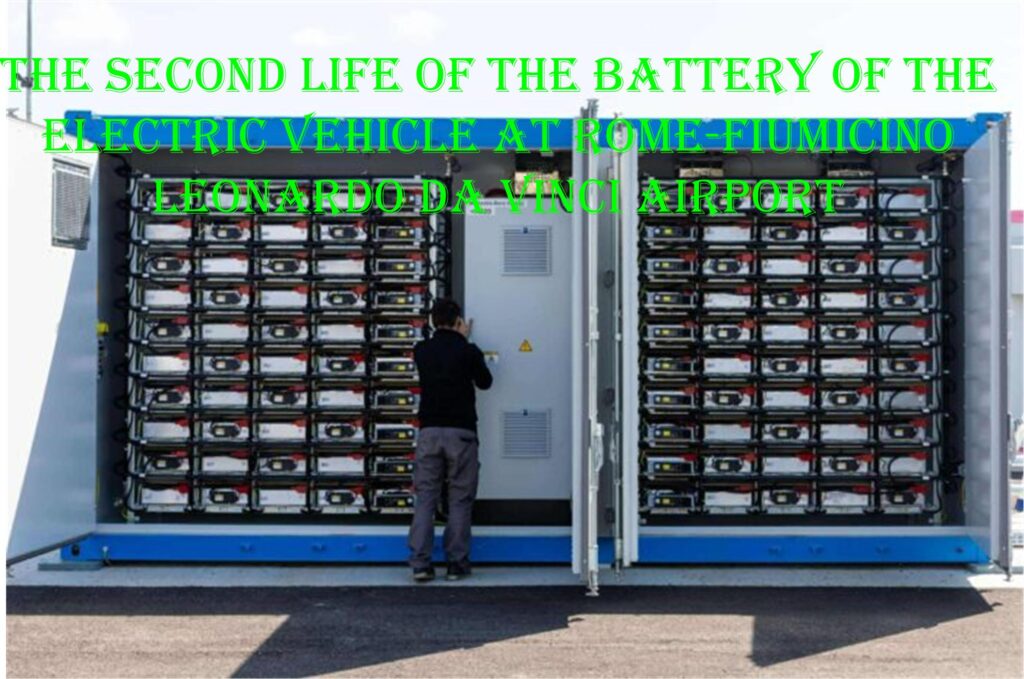

One of Europe’s most important airports has just inaugurated one of the continent’s largest energy storage systems using reused electric car batteries.

This is Rome-Fiumicino’s Leonardo da Vinci Airport, the largest in Italy and one of the ten busiest in the European Union. Based on renewable solar energy, this system aims to provide much of the electricity needed by the Roman airport.

- More than 760 batteries, many from the Nissan LEAF.

With 43 million passengers a year, the electricity consumption of Italy’s capital airport is colossal. With the aim of achieving carbon neutrality by 2030, it has taken another step forward with this newly inaugurated Pionner system. This project has been developed by the energy company Enel and Rome-Fiumicino Airport itself.

Pionner uses a solar farm with a total of 55,000 panels, which can generate 31 GWh of electricity per year. The energy collected by these panels is not used directly, but is stored in a huge storage system based on used electric car batteries, which supply energy to the airport through a cloud-based intelligent management system.

In total, the system has 762 battery packs from manufacturers such as Nissan, Mercedes, and Stellantis. Most of them, 84 in total, are from the Nissan LEAF, which are 30 and 40 kWh. According to the Japanese brand, despite their wear and tear, the batteries from what was the first electric car to be sold on a large scale still have a useful life of between six and seven years.

The total investment amounts to €5.5 million. The system is integrated into the “Solar Farm,” the largest photovoltaic self-consumption system at a European airport.

This system, they say, provides enough electricity to supply 3,000 homes for a day. In turn, they boast that it will help reduce CO2 emissions by around 16,000 tons over the next 10 years.

- Implications for fleet management.

To achieve net zero emissions in electric vehicles, the energy consumed must come from renewable sources such as solar or wind power.

The batteries from electric vehicles that are removed from the fleet can be used as stationary batteries in our facilities to supply renewable energy to the fleet’s own vehicles, our facilities, or the power grid.

Stationary batteries can be recharged with solar energy during the day, and electric vehicles can be recharged at night.

When an electric vehicle is taken out of service, we need to assess whether it is better to sell the vehicle or use the battery to store energy.

The residual value of an electric vehicle depends on factors such as the vehicle’s range, the condition of the battery, the price of new electric vehicles, the technology of new electric vehicles, mileage, and age.

Once the battery has been used for stationary storage, it must be recycled.

If our company wants to implement a stationary battery project and the batteries from the fleet’s electric vehicles are not sufficient, second-hand batteries or electric vehicles can be purchased.

The installation requires a large area for the solar panels and battery storage.

Before undertaking a stationary battery project, it is necessary to study how much energy we need to store. To do this, we need to know the number of square meters of solar panels, how many stationary batteries are needed, as well as the land, personnel, and necessary software and hardware, in order to determine whether it is economically viable.

In countries where there is no access to renewable energy from the electricity grid, this is a very interesting option for achieving net zero emissions.

Slide 3. Thank you for your time.

The class has developed the second life of electric vehicle batteries as energy storage at Rome-Fiumicino’s Leonardo da Vinci Airport, and the implications for fleet management, see you soon.

Bibliography.

https://www.agenzianova.com/es/news/Aeropuerto-de-Fiumicino%3A-llega-Pioneer–el-mayor-sistema-italiano-de-almacenamiento-de-energ%C3%ADa/

https://corporate.enelx.com/es/media/news/2021/10/enel-x-wins-eu-grant-for-pioneer

https://www.motorpasion.com/futuro-movimiento/uno-aeropuertos-grandes-europa-ha-sabido-sacarle-partido-a-viejas-baterias-coches-electricos-le-dan-energia-para-funcionar

https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/climate-energy/energy-storage-system-based-ev-batteries-launched-romes-airport-2025-06-03/

https://www.automobile-magazine.fr/nouvelles-energies/article/48364-un-aeroport-alimente-en-electricite-par-des-vieilles-batteries-de-voitures-electriques

The price of the training is 250 euros.

The training is asynchronous online, you can do it at your own pace, whenever and from wherever you want, you set the schedule.

Classes are video recorded.

Start date: The training can be started whenever you want. Once payment is made, you have access to the training.

The training is in English, subtitles and syllabus avalaible.

Other subtitles and video syllabus available: Arabic, Chinese, French, German, Indonesian, Italian, Japanese, Korean, Persian, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish, Thai, Turkish, Vietnamese.

All syllabus has been developed by the teacher.

Fill out the following form to receive course information, or write an email to:

Contact.

- José Miguel Fernández Gómez.

- Email: info@advancedfleetmanagementconsulting.com

- Mobile phone: +34 678254874 Spain.

Course Features.

- The course is aimed at: managers, middle managers, fleet managers, any professional related to electric vehicles, and any company, organization, public administration that wants to switch to electric vehicles.

- Schedule: at your own pace, you set the schedule.

- Duration: 25 hours.

- Completion time: Once you have started the course you have 6 months to finish it.

- Materials: english slides and syllabus for each class in PDF.

- If you pass the course you get a certificate.

- Each class has a quiz to take.

- English language, subtitles and syllabus.

- Other subtitles and video syllabus available: Arabic, Chinese, French, German, Indonesian, Italian, Japanese, Korean, Persian, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish, Thai, Turkish, Vietnamese.

-

Start date: The course can be started whenever you want. Once payment is made, you have access to the course.

Price.

- 250 euros.

-

You can pay by bank transfer, credit card, or PayPal.

Goals.

- Know the most important aspects to take into account when electrifying a fleet of vehicles.

- Learn about electric vehicle technology.

- Know the polluting emissions that occur when a fleet of vehicles is electrified.

- Know what technologies are viable to electrify a fleet of vehicles.

- Learn about real cases of vehicle fleet electrification.

- Know the history of the electric vehicle.

Syllabus.

- History of electric vehicle.

- Battery electric vehicle.

- History of the lithium ion battery.

- Types of electric vehicle batteries.

- New electric vehicle battery materials.

- Other storage technologies of electric vehicle batteries.

- Battery components.

- Battery Management System-BMS.

- Fundamentals of the electric motor.

- Battery degradation loss of autonomy.

- What is covered and not covered by the electric vehicle battery warranty.

- Battery passport.

- Battery fire of the electric vehicle.

- Causes, stages and risks of battery fire.

- Real cases of electric vehicle fire.

- Electric vehicle battery fire extinguishment.

- Measures to prevent, extinguish and control electric vehicle fires.

- Fire safety regulations for electric vehicle batteries.

- Impact of ambient temperature on battery performance.

- Which emmits more Co2, an electric car or a car with an internal combustion engine.

- The use of rare earth earths in the electric vehicle.

- Plug-in electric hybrids, a solution or an obstacle to electrify the vehicle fleet?.

- Fleet electrification with hydrogen vehicles.

- Cybersecurity of charging points.

- The theft of copper in electric vehicle chargers.

- Incidents at electric car charging points and their possible solutions.

- Batery swapping.

- The tires of electric vehicles.

- Electric vehicle, artificial intelligence, and electricity demand.

- The case of Hertz electrification.

- The case of Huaneng: The world’s first electrified and autonomous mining fleet.

- Consequences on the vehicle fleet of an electric vehicle brand going bankruptcy.

- E-fuels and synthetic fuels are not an alternative to decarbonize the vehicle fleet.

- How to avoid premature obsolescence of the fleet’s electric vehicles.

- Polluting emissions from brakes.

- Mileage manipulation to extinguish warranty early on electric vehicles.

- The importance of the electricity tariff in reducing electric vehicle costs.

- Electric vehicles cause more motion sickness than gasoline vehicles.

Training teacher.

José Miguel Fernández Gómez is the manager of Advanced Fleet Management Consulting, a consulting company specialized in vehicle fleet management and the owner of the fleet management channel on YouTube AdvancedfleetmanagementTube.

Since 2007 I have been working in fleet management consultancy and training for all types of companies, organizations and public administrations. With this course I want to make my experience and knowledge acquired during my work and academic career in this discipline available to my clients.

I carry out consulting projects related to vehicle fleet management and collaborate with companies developing products/services in this market. I have worked at INSEAD (France), one of the best business schools in the world, as a Research Fellow at the Social Innovation Centre-Humanitarian Research Group.

I carried out consulting and research activities in a project for the United Nations refugee organization (UNHCR), optimizing the size and management of the activities of the vehicle fleet, which this organization has distributed throughout the world (6,500 vehicles).

I worked as a fleet manager for five years, for Urbaser, which managed the street cleaning service in Madrid (Spain). I managed a fleet of 1,000 vehicles, made up of various technologies and types of vehicles such as: heavy and light vehicles, vans, passenger cars or sweepers.

I have completed all my academic degrees at the Polytechnic University of Madrid, one of the best universities in Spain, my academic training is as follows:

I hold a PhD in Industrial Engineering, with international mention, since I carried out research stays at the University of Liverpool (UK) and at the Royal Institute of Technology-KTH (Sweden).

I am also an Industrial Engineer (Industrial Management) and an Mechanical Engineer, and I completed a Master’s Degree in Operations Management, Quality and Technological Innovation (Cepade) and another Master’s Degree in Industrial Management (UPM).

I have publications in indexed magazines and presentations at international industrial engineering conferences.

Cancellations and penalties.

Once the course has started, the amount will not be refunded.