BEVs could have their day, but if the industry’s focus is on decarbonization, fuel cells are trucking’s future, according to a transportation futurist, who laid out the case for hydrogen. That’s an argument also backed by ATRI and Tier 1 suppliers.

NEW ORLEANS—The future of trucking is clean, but battery-electric transport is just a fantasy.

Transportation futurist Gary Golden told fleet leaders gathered here for Solera Outlook 2022 why he believes hydrogen will win out in the race to power their electric trucks and personal vehicles.

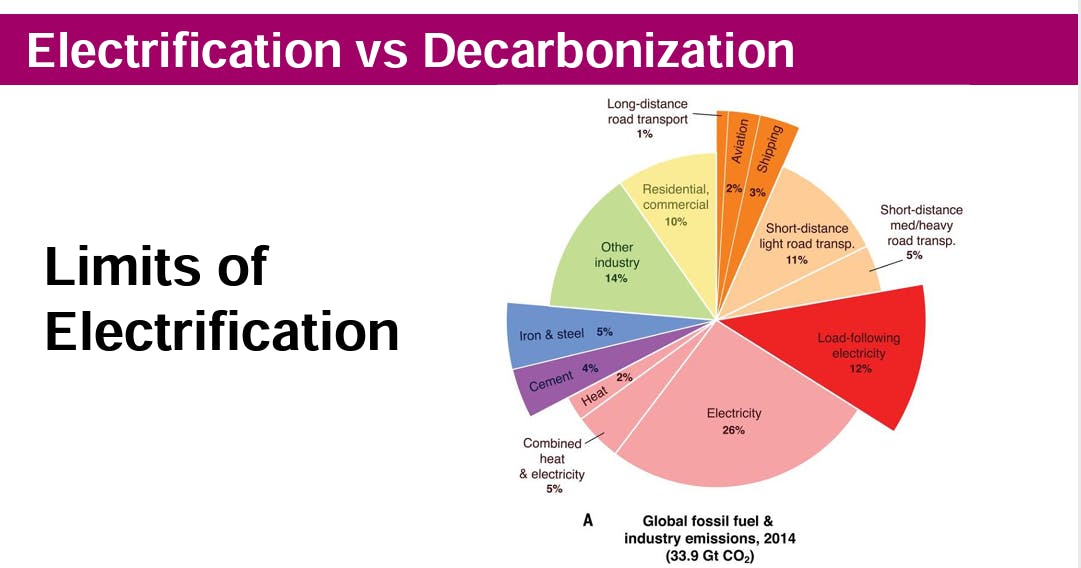

In the energy and transportation world, there is a debate between “pure electrification” and decarbonization, he said. The former focuses on electrifying everything—from transportation to manufacturing. “Decarbonization says we’re going to try to electrify as much as we can—but we can’t deny the role that molecule fuels play in the world,” Golden explained. “Molecule fuels, chemical bonds, deliver 80% of the world’s energy.”

“I believe that electrification—particularly in the transportation sector—is what we would call a fantasy wrapped in an illusion,” he said. “I don’t buy it. I don’t believe it. I don’t care what anybody says. I don’t care when a person is like, ‘I have an electric car. I love it.’”

Hydrogen fuel-cell trucks are the most decarbonized freight vehicles, according to a recent American Transportation Research Institute report. “Battery-electric trucks are only about 30% cleaner than diesel trucks,” Daniel Murray, ATRI SVP, said during a breakout session at Solera’s first user conference since expanding its fleet solutions through several recent acquisitions.

During his keynote speech that morning, Golden said the future of EVs is about the motor, not the battery. “How we deliver the electricity to that motor is of debate,” he explained. “But it’s the motor that defines the EV.”

The EV conundrum

Golden asserted that the cheapest EV powertrain is a small battery, hydrogen fuel cell, and capacitor. “Because when you look at the mature, full-picture, long-term cost curve per kilowatt of a battery versus a fuel cell, fuel cells will be cheaper than batteries,” he said. “Not today, but in a mature manufacturing world, fuel cells will always be cheaper because they don’t have the mineral requirements that batteries do.”

Murray noted that building an electric truck is less green than producing diesel equipment. “Electric trucks are six times more polluting than a diesel truck,” he said. “Why is that? You need cobalt, lithium, nickel, manganese to make these lithium-ion batteries. And that’s very expensive to mine that out.”

Class 8 BEVs are limited to 250 miles with the largest batteries, according to ATRI’s research. The battery’s weight and size reduce freight capabilities, too, Murray noted. The replacement batteries, which Murray said could cost as much as a new diesel tractor, would need to be replaced every four to seven years.

“And there’s no place to charge these,” Murray said. “Elon Musk stopped bragging about building a 600-mile-charge truck. You haven’t heard that in two years because that is a physical impossibility. The best you’ll get on a charge—which will take you two to four hours to get to 80%—is a 200-mile trip.”

With trucking facing a driver shortage and most drivers paid by the mile, Murray said: “Now you’re going to tell your drivers that instead of driving 500 miles, I need you to stop every 150 to 200 miles. You’re not going to get paid, but I need you to stop and charge for four or five hours.”

Another recent EV trucking study by the North American Council for Freight Efficiency said that half of U.S. regional and short-haul Class 8 trucks are ripe for electrification today. NACFE said that half of the 930,000 Class 8 regional operations could go electric. This would be nearly a quarter of the roughly 2 million Class 8s serving the U.S. today.

How do you charge an entire fleet at night?

But futurist Golden doesn’t buy that infrastructure can be built out to support commercial or consumer battery charging. EV proponents suggest that “everyone will just plug in at home,” he said. “That’s a lie. When you look at the people in the world and where they put their car at the end of the day and where fleets go, only a small percentage of them are in a spot where it’s easy to just plug in.”

As more EVs are built, hydrogen will be a simpler and cheaper way to fuel trucks and cars, according to Golden. The precious materials that go into batteries are only found in a few countries, while hydrogen is abundant, he added.

“What I think is happening in your world in terms of that energy transportation story is part of a longer arc of the decarbonization of fuels,” Golden told hundreds of Solera customers.

Human society used to rely on carbon-intensive materials such as wood and coal for fuel, he said. “Then, we found these hydrogen-rich bonds in oil and gas,” he added. “What we’re entering is the era of hydrogen-rich, electrochemical energy conversion.”

Internal combustion engines have multiple stages of mechanical output that lose energy at each step, Golden explained. While hydrogen fuel cells convert the chemical energy of hydrogen into electricity in one step. “Not multiple steps—one step,” he emphasized. “And it does it without moving parts. So it doesn’t wear-and-tear. It doesn’t break.”

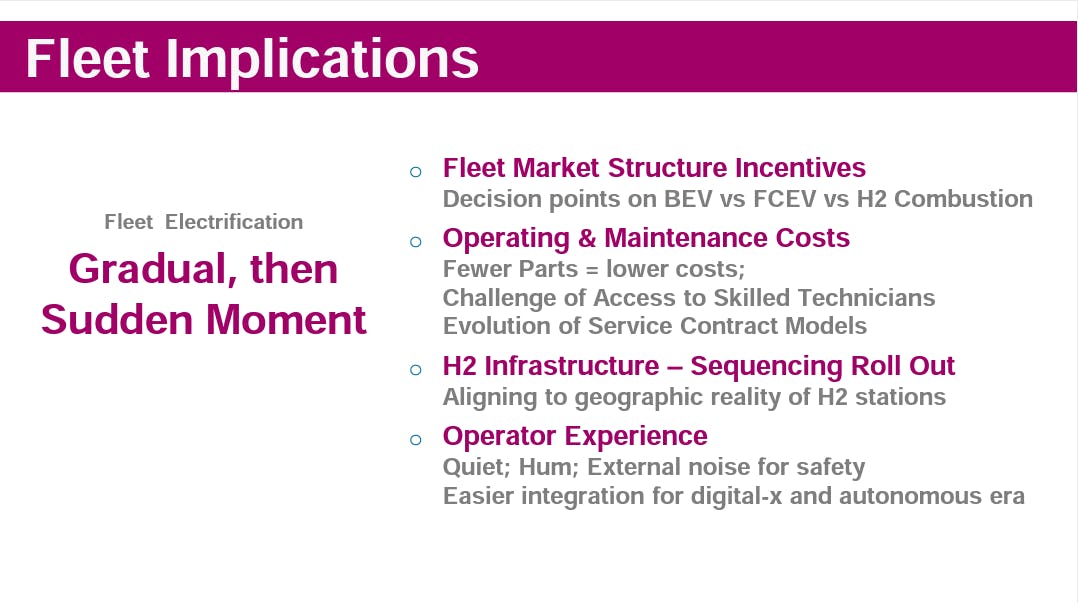

He said the future of heavy-duty trucking energy is a fuel-based electric motor. “There will be EVs built for the next 10 to 15 years, maybe longer for short-haul. But we need fuel cells because it’s less weight and there’s more space for cargo and cabin capacity.”

Listen to Tier 1 suppliers, not Tesla

“If you want the signals, you don’t look to see what Elon Musk is saying. You look at what the Tier 1 system integrators are building,” Golden explained. “From 2023 to 2028, all of them are bringing hydrogen fuel cells online.”

Kenworth has a fuel-cell truck, which it developed with Toyota, in pilot tests. The most recent major fuel-cell partnership is between Cummins and Daimler Truck North America.

He predicted market dynamics would turn green hydrogen—energy produced through solar, wind, geothermal—into a new energy commodity. “Chile and Australia are the world’s largest lithium producers,” Golden noted. “When you look at their energy-use stories, the only thing you hear from Chile and Australia is their green hydrogen strategy. Because once you send that to them abroad, it doesn’t come back.”

He said hydrogen infrastructure projects could help fleets plan. “If the region you service or where your business is located has no kind of hydrogen corridor on the map, your future transition point is farther out,” he said.

The first regional hydrogen stations will either produce the fuel on-site or deliver it by truck. Eventually, cities would have high-pressure pipelines, which Golden said would be the easiest, safest way to fuel hydrogen stations.

By Josh Fisher

Source https://www.fleetowner.com/