Giant crawler-transporter team is gearing up for what might be the most crucial last-mile delivery of the 21st century: hauling the multimillion-pound launch system that could pave the way for human spaceflight back to the moon and on to Mars.

How has NASA kept a vehicle 80 times larger than a fully-loaded tractor-trailer running since the Johnson administration? A stellar maintenance program. And lots of lubrication.

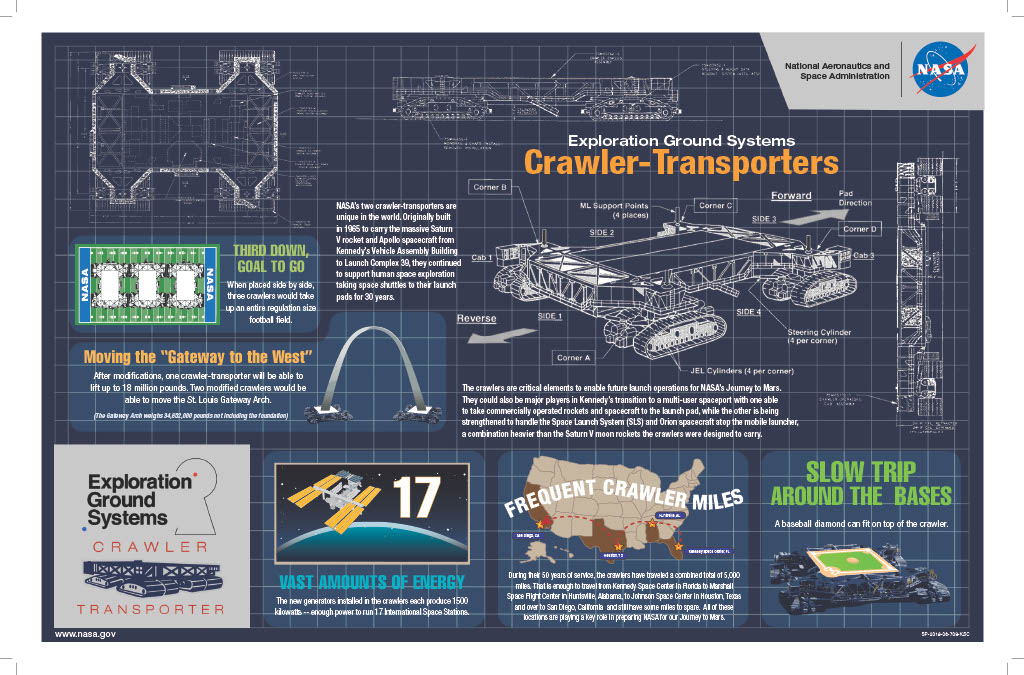

Anyone who works on heavy equipment knows the importance of a good preventive maintenance schedule. There are few heavier pieces of equipment in the world than NASA’s two crawler-transporters, which first hauled Saturn V rockets to a Kennedy Space Center launchpad during the Apollo era of spaceflight.

This spring, 55 years after transporting its first rocket, NASA will use a strengthened Crawler-Transporter 2 to move its most enormous load yet: the 380-ft. Mobile Launcher 1 with the Space Launch System (SLS) atop it. That SLS is a mighty rocket-launch tower that weighs 11.3 million lb. This could be one of the most critical last-mile deliveries this century.

This April or May, the crawler will roll underneath the mobile launcher constructed inside the Vehicle Assembly Building, pick it up, and slowly carry it and the Orion spacecraft about 4 miles to Launch Pad 39B for the maiden launch of NASA’s Artemis program, which will set the stage for the space program to return to the moon and farther—including Mars.

“There’s no sunroof in the VAB—so we can’t launch out of there,” John Giles, engineering operations manager for development and operations for NASA’s crawler-transporters, told FleetOwner. “So you’ve got to get to the pad. And this is the only way to get there. If we’re not working, it’s a bad day for NASA.”

Giles joined NASA out of college 33 years ago. After a decade working with space shuttle payloads, he worked with expendable launch vehicles for 10 years before working in human spaceflight. Giles joined the crawler team in 2011.

Sam Dove, a crawler-transporter engineer, grew up on a West Virginia farm around a lot of heavy equipment before joining the U.S. Air Force. After the service, he got his engineering degree and was hired to work in Kennedy Space Center’s design engineering team in 1988. Ten years later, he joined the crawler team.

“I’ve always been around a lot of heavy equipment,” Dove, whose father was a longtime service manager for Worldwide Equipment, told FleetOwner. “This is kind of the ultimate heavy equipment.”

‘It’s really like anything else—except it’s bigger’

“Since 1965, the crawlers have been here,” Dove said during a video interview from Kennedy Space Center at Merritt Island, Florida. “It has been used by several generations of engineers and technicians to move Saturn Vs, to move space shuttles, and now we’re gonna move SLS rockets.”

Dove is part of the Jacobs Engineering Group, an operations support contractor for the NASA Exploration Ground Systems program at Kennedy. The Jacobs team includes several engineers and technicians focused on transporting flight and ground equipment around the space center. The team includes veteran engineers like Dove and the next generation of mechanical engineers, including Breanne Rohloff. In 2019, at 22 years old, she became one of the first women ever to operate a crawler-transporter. [See sidebar for Q&A with Rohloff and Dove.]

As NASA sets its sights on human space travel beyond the moon, Dove expects the crawlers to keep running well into this century, providing more opportunities for future engineers to be part of NASA’s rich pre-launch history. The engineering team’s intense preventive maintenance program is vital to keeping the transporters still crawling deep into this century.

“Over five decades of doing this, they have a pretty good idea of what needs to be done on a regular basis, year after year,” Giles said of the crawler team of engineers and technicians.

The team has a full, monthly maintenance program for the machines. Dove rattled off a long list of vehicle systems his team regularly checks off the top of his head. “It’s really just like anything else—except it’s bigger,” he added. “You have to keep it lubricated.”

That’s a lot of regular maintenance and lubrication over 57 years. It can be like caring for a classic car. “After so many years, some systems need to be rebuilt,” Dove explained. “If you have a ’72 Camaro, some of those parts are going to be a little hard to get, so you might have to upgrade and get something new. So that goes along with the maintenance program.”

For example, Giles said NASA needs to replace the crawler’s steering cylinders after the next rocket launch. “Right now, we’re in the process of having a company build us a full lot of new steering cylinders that are quite specialized. So it’s a very big-ticket item.”

“As Sam said, one of the big reasons that this thing’s still operating after being built in the mid-’60s is lubrication,” Giles said. “Everything that’s moving gets lubricated. And it probably also gets an accelerometer or a strain gauge put on it, too, so it can be monitored.”

The crawler has two 2,500-gallon diesel fuel tanks filled up before any trip. The fuel powers two 16-cylinder Alco engines and two 16-cylinder Cummins Power engines. The crawler’s mpg is more easily measured in fpg: 32 feet per gallon, which equates to about 165 gallons per mile.

It’s a long last mile to the launchpad

“I think the crawlers are pretty much the last vehicles around that actually do this type of work,” Dove said.

Each crawler has eight tank-tread-like belts with 57 shoes. Each shoe weighs 2,000 lb. and lasts about 1,000 miles. Dove said he could tell the current shoes on the crawler, last replaced in 2004, are nearing their final runs after years of hauling millions of pounds at a time.

“In a tractor-trailer, you get almost instantaneous steering. With the crawler, you have to see where it’s going. You have to steer, wait, and then everything catches up. Then you steer a little more and wait. Plus, there is a limit to how much you can steer at one time. You have to have your speed right, you have to be positioned right, you have to get the steering in at the right time. And that probably takes little patience,” he said with a laugh.

It takes a big team to operate the crawlers, Dove said. Along with the driver in the cab, several engineers monitor its movements from a control room. Some engineers are in charge of making sure the crawler stays level as its giant caterpillar tread slowly moves it forward. Other NASA personnel keep an eye on fluids in the engine rooms and pump rooms.

“When you come into or out of a facility or the pad, you’ll have drivers in both ends because you have to kind of steer it like a hook-and-ladder fire truck,” Dove added. A laser docking system assists operators in getting the crawler within an eighth of an inch of its destination.

Giles said the new mobile launcher was already hauled to the launchpad during three test runs.

“Next month, we’ll pick up the mobile launcher with the launch vehicle. We’ll roll to the pad for what we call a ‘wet dress rehearsal,’ which means we’ll make all the physical connections. We’ll make all the communications connections. And we’re even going to fuel it—that’s why it’s called a wet dress rehearsal. So we’ll actually put the fuel in the vehicle and then see if we have any issues. Then we’ll roll it back. Any issues we have will get fixed. Then we’ll actually roll to the pad for a launch about a month later. So we’ll actually have quite a few rolls under our belt before we do the real thing.”

NASA’s new Space Launch System is just weeks away from making history on the launchpad in Florida. Before astronauts can again step on the moon or even envision traveling to the Red Planet, their space vehicle needs its own ride—just like so many rockets and space shuttles from NASA’s rich spaceflight history.

“The crawler-transporter is right in the middle of everything,” Dove said. “It’s a very special piece of equipment. If there’s something moving on the Space Center, the crawler is usually involved in it. I just can’t tell you how much this job means. It’s good duty.”

Q&A with two crawler-transporter engineers

The Jacobs Engineering Group’s senior crawler-transporter engineer, Sam Dove, and its youngest engineer, Breanne Rohloff, talk about operating one the largest pieces of equipment in the world. NASA conducted the following Q&A, which has been edited for clarity.

What’s it like to be a NASA crawler driver?

Dove: It dominates whatever’s around it. You can feel the massive machine as it comes by; it shakes the ground a little bit. It would just amaze you; the size and the complexity of the world’s biggest tracked vehicle. Think of something that’s moving very slow … around 1.2 to 1.3 kph … moving this massive rocket down the road. It’s fun to get up every day and come out and work on the crawler.

Rohloff: Mind-blowing. When I looked up at the crawler moving for the first time I was in awe, just taking in the size and power it has. Every day is different on the crawler, and there’s a lot of parts and pieces to learn and become proficient in.

How many people does it take to operate?

Rohloff: The team is about 30 engineers and technicians that huddle up a few hours before a roll to the launch pad to review the operation, talk safety, and discuss who’s in charge of each task. We switch positions throughout the roll to keep fresh eyes on the systems, we all work together to execute a successful rollout.

Dove: There are at least 10 engineers/drivers and 20 technicians on or around the crawler at any time. You’ll have an engineer that is the test conductor, an engineer operating the jacking equalization and leveling system, and two engineers as the primary and secondary drivers. Technicians will staff the engine rooms, the pump room, and roving hydraulics positions. There will also be four to five technicians on the ground to help with guidance and to watch over systems/equipment. It’s a specialized team for the world’s largest tracked vehicle.

How does the team start the rocket mover?

Dove: The first thing that lets you know we’re starting up is the use of compressed air to start the ALCO engines. Then, the second set of engines start. After that, power transfer occurs. Then the hydraulics and support systems are started.

It really has a sound all of its own. You need to be attuned to what the equipment sounds like, and if it’s not running right, you can almost immediately tell when you need to start looking at something.

Rohloff: Hauling a billion-dollar spacecraft to the launch pad starts just like any other vehicle that moves—with startup sequences in the control room, power transfer, the push of a button, and the twist of a knob in the cab.

The crawler only goes 1.5 kph. Is that speed monotonous?

Dove: Oh, no. Boredom is not something that you have on the crawler. You’re watching where you’re going, where you’ve been, where you’re at, the speed, what your steering angle is, and many other parameters. You must be aware all of the time because if the crawler catches you not paying attention, it will remind you.

Rohloff: We may crawl slow but that doesn’t equal an easy drive. Driving the crawler is a bit like steering a large ship, and when the rocket is onboard, it will be like steering a large ship with a skyscraper on top. You’re constantly making small steering corrections, even when you’re moving straight.

Dove: Since the vehicle is only designed to make six-degree turns, drivers need to start turning well in advance when approaching curves on the Crawlerway—the 6.7-km (4.2-mile) river-rock “road” the crawler travels on to the launch pad.

Rohloff: Being a certified crawler driver is not just learning how to drive the machine. You must also understand and be able to operate the crawler’s other major subsystems. After one to two years of on-the-job training, we drivers-in-training will be on our way to becoming a certified crawler driver.

What’s surprising about a rollout of the rocket to the launchpad?

Dove: The amount of planning and coordination that goes into each operation.

Rohloff: We’re also constantly on the lookout for wild animals. Bobcats, alligators, turtles, snakes, wild hogs, coyotes, etc.

You just sit there thinking, please don’t move into the Crawlerway. If they do, you need to stop the crawler and get the wildlife out of the way.

Dove: There was a 12-foot alligator that was under one of the trucks. We had to call the wildlife officer to come and pull that gator out.

The whole ride down the Crawlerway leads up to the most crucial and technical moment when the Crawler approaches the launchpad?

Dove: The crawler transits up the pad slope (ramp) and then places the rocket, with its launcher, precisely onto the launch mounts.

Rohloff: And that’s when things get exciting and everyone becomes even more focused.

Dove: By far the most stressful part of any rollout is going up the pad slope. All the systems have to work, the team has to be on top of its game for the operation to be successful.

By Josh Fisher

Source https://www.fleetowner.com/