For years, the U.S. heavy-duty trucking industry has been preparing itself for the inevitable changeover to zero-emission vehicles (ZEVs).

The impetus was stricter federal emission regulations, which has evolved into 15 states incrementally limiting the future sales of new commercial trucks with internal combustion engines.

As larger fleets vet the first wave of ZEVs, battery-electric trucks, they are finding motivation to adopt in the form of increased operational benefits, from lower total cost of ownership and fuel costs to better drivability and comfort (quieter and less vibrations). With those advantages, fleets must also take on new complexities, chiefly in how to charge these trucks’ batteries to leverage at times of the day when electricity is cheaper, factoring in optimal utilization.

While some fleets became early adopters for battery-electric vehicles a few years ago and have cracked some of the charging infrastructure puzzles, the funding, installation and operational challenges will confound many over the next decade.

Now, as battery-electric truck manufacturers ready themselves to scale up production, fleets must also start preparing for the introduction of fuel-cell electric trucks (FCETs), which use onboard hydrogen to generate electricity. FCETs are similar to BEVs in that a battery powers a motor and they leverage regenerative braking, but they also haul sophisticated power plants to harvest energy from energy-dense hydrogen atoms, creating electricity and water in the process.

Because they do not pull energy directly from the grid, these trucks will be crucial to helping fleets meet emissions goals while not monopolizing a region’s energy capacity.

“It’s very clear that heavy vehicles with high utilization will always be a challenge on batteries, no matter what your battery cells look like, or no matter how you plan to charge them, or where you plan to get all that electricity,” said Craig Knight, CEO of fuel-cell powertrain maker Hyzon Motors. “Once you have a lot of a lot of trucks on batteries. It really becomes a grid infrastructure issue.”

The transportation industry seems to be aware of this, and the sleeping giant that is hydrogen. The McKinsey Center for Future Mobility estimated that the commercial fuel-cell electric vehicle (FCEV) market will increase 34% annually until 2030.

Hyzon, based in Rochester and spun off from Singapore-based fuel cell manufacturer Horizon, projects that its network of factories across the globe will produce 40,000 fuel cell vehicles (including buses) per year by the end of 2025. The parent company has 17 years of fuel-cell experience and Hyzon, which is about to go public after a business combination with Decarbonization Plus Acquisition Corp, recently announced it will be making e-axles with up to 97% motor-to-wheel efficiency.

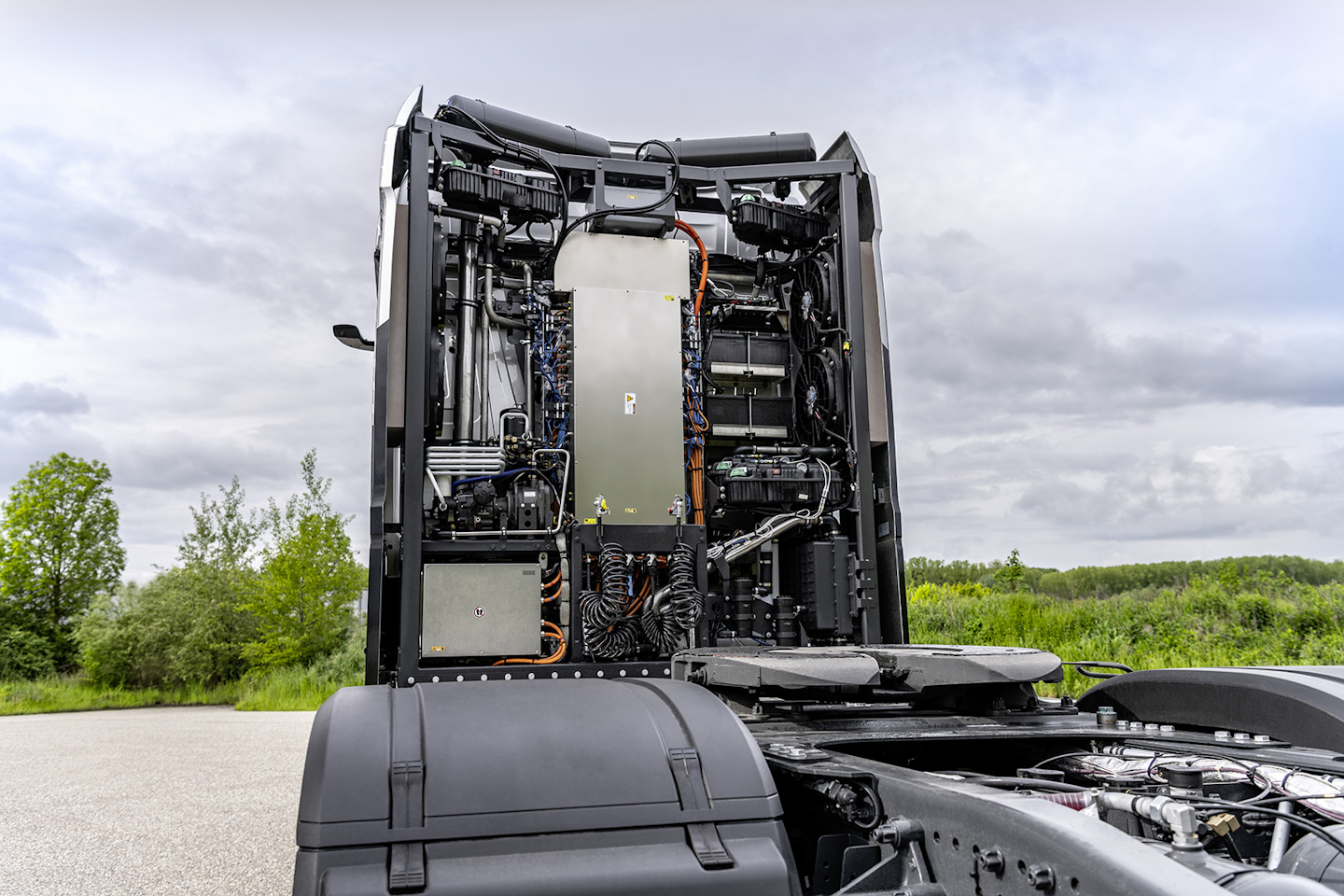

Under the (cabover) hood of a Hyzon Motors test truck reveals the fuel cell stack.Credit: Hyzon Motors

And it is also vital that fleets get a head start on how to handle and maintain these trucks now so that in 2025, or whenever FCETs take hold, they are not scrambling to understand the technology while competitors are hauling with hydrogen power and reaping the benefits. And as several truck makers’ executives can attest, FCETs will be here before you know it.

The major advantage over battery-electric powertrains is the enhanced range.

For example, the extensively tested battery-electric Freightliner eCascadia (production slated for late 2022) will have a range of up to 250 miles per charge, whereas parent company Daimler Trucks’ prototype FCET, the Mercedes-Benz GenH2 Truck, targets a range of 625 miles. The GenH2 is currently undergoing “rigorous” testing according to Daimler Trucks, with public road testing this year and customer testing in 2023. Four years after that, Daimler Trucks expects to deliver these FCETs to fleets.

“The hydrogen-powered fuel-cell drive will become indispensable for CO2-neutral long-haul road transport in the future. This is also confirmed by our many partners with whom we are working together at full steam to put this technology on the road in series-production vehicles,” said Martin Daum, CEO of Daimler Truck AG.

The most notable partner Daimler Trucks is working with is one of its biggest competitors: Volvo Group. The two OEMs, knowing that developing fuel-cell based transport takes too much capital to approach alone, have teamed up to form the joint venture called cellcentric.

Daum looks at the startup as a child, one born lucky enough to have parents with plenty of resources. “They don’t have to kick out headlines just to attract more investors and get a little more money to survive the next year,” Daum explained of cellcentic. “They have extremely strong and committed parents, they have an absolutely strong financial base, and they have a commitment from both parents to invest whatever it takes to get to zero emissions and to see the production of zero-emission components. And they have a very strong know-how base.”

Cellcentric has about 300 subject matter experts working at sites in Stuttgart, Germany and the outskirts of Vancouver, B.C., and has about 700 patents filed.

“We see a clear roadmap for execution both when it comes to technology and commercialization,” explained Martin Lundstedt, Volvo Group president and CEO.

Anterior view of the Gen2 fuel cell electric truck.Credit: Daimler Trucks

Partnerships adding up

Cummins, a company largely responsible for diesel’s dominance over the last century, has also pivoted to fuel cells, while also exploring CNG/RNG and improving on its diesel engines. In 2019 Cummins acquired Hydrogenics, a provider of fuel cell and hydrogen production technologies. More recently, the Class 8 powertrain manufacturer announced a partnership with Navistar to build an FCET from an International RH Series template.

This is not the only OEM Cummins is working with, though the two have an 80-year relationship, so that history of collaboration is likely to accelerate, or at least not slow down, advances. And with alliances being formed all over the industry, limiting the amount of impediments clears a path to successful customer rollouts.

Hino, Isuzu, and Toyota are also partnering, and Paccar brands Kenworth and Peterbilt are also active.

The first step, getting fleets to take hydrogen seriously, seems to be building momentum.

“We have definitely seen an increase in interest from customers in the past year,” Amy Adams, Cummins’ vice president of Fuel Cells and Hydrogen Technologies, told FleetOwner.

“The attractive parts of the fuel-cell vehicle for now is that it’s much more similar to your operation of a diesel vehicle or natural gas vehicle–15 minutes for a fuel up,” Adams said.

Cummins will begin testing fuel cell trucks with four major fleets by the end of the year, Adams said.

“Fleets are thinking about things like maintenance, driver experience, driver training, safety, and then cost,” Adams said. “They’re all interested understanding these things.”

Werner Enterprises is one of those fleets.

“Testing the vehicle in real-world conditions will help paint a full picture of how the system performs over challenging road conditions, including both hot and cold climates,” said Scott Reed, senior vice president of fleet purchasing and maintenance at Werner Enterprises last year. “In addition to that performance data, we are excited about the opportunity to provide feedback from Werner professional drivers, mechanics and fleet management to help the project team develop a comprehensive total cost of ownership analysis.”

Catching up to Europe

This detailed and serious examination of FCETs bodes well for continuing hydrogen’s momentum in the U.S. Until recently, Adams noted that outside of California, the U.S. cared little about fuel cells, while in Europe “everyone’s talking about hydrogen.”

“Europe is substantially ahead on hydrogen: infrastructure wise, and in terms of customer validation, and acceptance,” Knight noted.

Hyzon has recently paired with two regions in the Netherlands, Utrecht and Groningen, to deploy FCETs. Utrecht wants to deploy 300 heavy-duty hydrogen-powered vehicles and 1,500 light fuel-cell electric vehicles by 2025. Hyzon will supply Groningen with 15 medium and heavy-duty FCETs by the end of this year.

The problem for every region has been hydrogen’s cost. The monetary and energy costs of producing hydrogen for vehicles is currently steep, but on the verge of declining in Europe. Electrolyzer maker Nel ASA said they could produce green hydrogen (produced from renewable sources) for $1.50/kg by 2025. The current costs for green hydrogen in Europe is $3/kg t $6.55/kg, according to the European Commission.

Europe has built out its renewable infrastructure over several decades, making the coveted green hydrogen (produced from renewable sources) more readily available. In the U.S., hydrogen is more gray, coming from natural gas.

“Almost all the hydrogen [in the U.S.] is made from steam methane reforming from natural gas, and it’s less costly than green, generally speaking, but the cost of renewable energy has come down considerably. We see the same thing happening in the hydrogen production side, and also on the fuel cell side.”

Cummins recently signed a memorandum of understanding with KBR to produce green ammonia, or ammonia sourced from renewables. Ammonia molecules (NH3) are composed of one nitrogen atom and three hydrogen atoms and are being looked at as a sustainable way to store and transport hydrogen.

Incentivizing progress

A major driver to drop costs in the U.S. will be government grants and incentives. Along with potential funding opportunities through the proposed $2.25 trillion American Jobs Plan, the Department of Energy is making $100 million available over the next four years through SuperTruck 3, which will focus on electric vehicles.

Secretary of Energy Jennifer Granholm specifically mentioned fuel cells, notable because the technology has often taken a backseat to BEVs.

“We don’t think it should be a fight: the battery people against the fuel cell people,” Adams said on the issue of funding. “You should let the best technology win. If the policies incentivize innovation, then industry will do what it does well and develop solutions. We don’t think that the government should be dictating technologies, per se, but should try to dictate outcomes.”

Scaling up manufacturing and finding all the necessary resources will also be difficult, as the current chip shortage illustrates

“We’re early in the technology, and ramp-up cost is a big function as well,” Adams said. “As an industry, we need to drive the cost down, because you can’t have too much proliferation. You need to home in on those sweet spots in terms of applications and optimize for them.”

Knight believes Hyzon will be able to demonstrate cost parity with diesel in the next 18 months in two or three regions. He pointed to Australia as a strong candidate and did not rule out California as another, where Hyzon will test its solution this year.

A key to making FCETs successful is buy-in from both large and small fleets, and Hyzon plans on offering a service-oriented structure.

“It has to sell as an ecosystem,” Knight said. “Customers need hydrogen and they need service and support, financing and insurance and compliance stuff, and safety all around the vehicles as well.”

By John Hitch

Source: https://www.fleetowner.com/

CUT COTS OF THE FLEET WITH OUR AUDIT PROGRAM

The audit is a key tool to know the overall status and provide the analysis, the assessment, the advice, the suggestions and the actions to take in order to cut costs and increase the efficiency and efficacy of the fleet. We propose the following fleet management audit.