EVs aren’t coming—they’re here.

Several classes of battery-electric vehicles, the charging infrastructure needed to support them, and all manner of associated technologies are starting to flood the marketplace.

And through all this noise, trucking industry stakeholders are left to try and figure out what works for their routes and operations and what doesn’t—and most importantly what they can afford.

Fleets can take this to the bank: The decision to electrify even part of a freight or vocational operation is an expensive one—regardless of whether you utilize Classes 1-3 vehicles for last-mile delivery, a bucket truck as a utility vendor, or would like to run regional or longer haul routes one day with some of the first big breakthrough electric Class 8s from Freightliner, Volvo, and Kenworth.

As an example, for the biggest Class 8 EVs, the cost of an eCascadia from Freightliner, Volvo’s VNR Electric, or Kenworth’s T680E—depending on how they’re configured—is conservatively two or three times as much as an equivalent diesel-burning tractor, which can run in the range of $140,000, industry sources told FleetOwner. So do the math.

Then again, the advances with these electrics—and others like European EV maker Volta’s medium-duty battery-electric truck (it had its battery performance tested last month in the Arctic Circle) and years-delayed Class 8 Tesla Semi, which Elon Musk now says will come out in 2023—mean more and more competitors still will come to the marketplace. Prices will drop because of this. Also, while early adopters are seeing high-dollar initial outlay, stakeholders such as electric utilities project reasonable total cost of ownership (TCO) as time goes on.

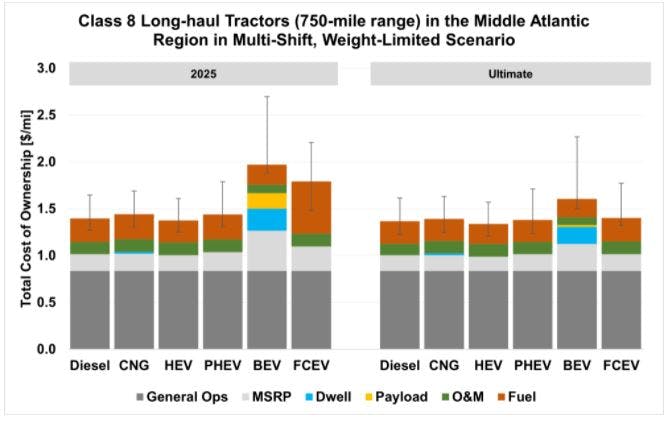

In fact, a National Renewable Energy Laboratory study, results from which were released last fall, showed that electric and hydrogen fuel cell-powered vehicles will have comparable or lower TCO than trucks with internal combustion engines (ICE) by 2025.

The study measured TCO for Class 8 long- and short-haul trucks and Class 4 parcel-delivery vehicles for six different powertrain technologies: diesel, diesel hybrid electrics, plug-in hybrid electrics, compressed natural gas (CNG), battery electrics, and hydrogen fuel-cell electrics (FCEVs).

See also: Fleet electrification provides great opportunity—if done right

Costs measured in the study included purchase price, fuel, operations and maintenance, driver wages and benefits, insurance, tire replacements, permits, tolls, dwell-time costs due to refueling/recharging and lost payload capacity from heavier advanced vehicle powertrains.

The findings also show that battery electrics may be best for shorter ranges or when dwell time is less of a concern. FCEVs may be better for longer ranges or when greater uptime is needed. A session at Work Truck Week 2022 in Indianapolis in March yielded the same consensus from panelists.

The TCO case can be made. And EVs are selling, so an adoption wave already is taking place in the market.

According to the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy, sales of new light-duty EVs, including plug-in hybrids, nearly doubled from 308,000 in 2020 to 608,000 last year. However, sales of light-duty fossil fuel-burning vehicles in the same classes only increased 3% during that same period.

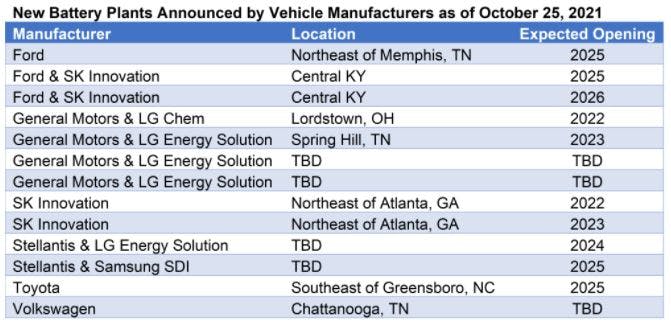

According to the same federal government office, 13 new EV battery plants are planned in the U.S. within the next five years in addition to the plants that are already in operation in the U.S. Of the 13 planned plants, eight are joint ventures between automakers and battery makers.

An even newer Energy Department study, released March 7, shows that by 2030, nearly half of medium- and heavy-duty trucks will be cheaper to buy, operate, and maintain as zero-emission vehicles than traditional diesel-fueled equivalents.

The costs, however, don’t just include the trucks. Consider these two words: charging infrastructure, which is more of a wild card in the decision about whether to adopt. Outside California, your fleet will have to bear much of the cost of plug-in stations located at HQ—with the help of limited but growing incentive programs.

It’s not like there’s much of a nationwide charging infrastructure for anything that doesn’t have a Tesla nameplate. The average Sheetz or Royal Farms or even Love’s or TravelCenters of America has room and plug-in stations for passenger EVs, but they don’t yet have the parking space for commercial EVs to “fuel” for the hours necessary. Faster charging technologies are only just emerging, and a prospective U.S. government-funded national charging network is still years away.

A lot of early adopting fleets with “range anxiety” are doing their homework. If your fleet chooses electric vehicles, plan your routes carefully, these fleets report, or thoughtfully review the ones you do run. While batteries on all-electrics have come far, range in optimal conditions is still limited to about 250 miles if not less. Until range with these batteries improves, the “use cases” at this writing for EVs might be limited.

Today, studies show that the EV population is small, representing less than 1% of the total commercial vehicles on the road in the U.S. and Canada. But projections are that by 2027, EVs will grow to 22% of the market and will reach 40% by 2035. At that point they will grow at 3% per year until 2040.

That means, under certain conditions, the technology is available and ready, with help of good research and telematics.

So, is your fleet ready to consider adoption? If you’re a fleet executive or manager, here’s how to direct some of your research.

It’s about the money: Funding the networks

The good news is the federal government is thinking and planning a lot around sustainability—and for commercial solutions that don’t involve diesel-burning internal combustion engines—so the Biden administration is planning for a federal charging infrastructure network to go along with any incentives that are available from states such as California or through electric utilities so fleets can build their own.

In mid-February, President Biden and the Departments of Transportation and Energy pledged $5 billion over five years for a national EV charging network, made possible by the massive Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act that Biden signed into law last fall. The massive law provides more than $7 billion for electric vehicles, including the creation of this nationwide network of 500,000 charging locations.

See also: The truth is EVs are already here

A joint energy and transportation office, through its website, DriveElectric.gov, will assist states with funding and electric vehicle infrastructure deployment plans. It’s the states’ first large-dollar financial assistance for charging stations outside their own efforts—with California leading the way—and private and utility company investment. The funds will be available through the new National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure (NEVI) Formula Program. The money will help states set up networks of EV charging stations along designated alternative fuel corridors, particularly through the already-existing Interstate Highway System.

The total amount available to states in fiscal year 2022 under NEVI is $615 million, and states must submit an EV Infrastructure Deployment Plan before they can access these funds. A second federal competitive grant program designed to further increase EV charging access in locations throughout the country—particularly in rural and underserved communities—will be announced later this year.

“A century ago, America ushered in the modern automotive era; now America must lead the electric vehicle revolution,” Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg said at the mid-February announcement of the charging network. Energy Secretary Jennifer M. Granholm added, “We are modernizing America’s national highway system for drivers in cities large and small, towns and rural communities, to take advantage of the benefits of driving electric.”

The Biden administration’s ambitious sustainability goal calls for half of all U.S. vehicle sales—cars, commercial vehicles, school buses, transit, everything—to be ZEVs, or zero-emission vehicles, just eight years from now.

‘Thought capital’ for electrification

In the last five years, California has become the incubator of electrification—mostly out of necessity.

In 2020, the greenhouse gas (GHG) problem there was worse than just about anywhere in the U.S. The smog problem in Los Angeles alone, home to much commercial trucking activity, especially around the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, was the worst it has been in the last 30 years.

And commercial vehicles play a huge part. They represent 3% of all vehicles on California’s roads, according to the California Air Resources Board (CARB), but emissions from trucks make up half of all pollution from motor vehicles in the Golden State, which is countering with a lofty goal of its own—cut emissions there by 75% by 2030. CARB’s standards have long been known as the strictest in the nation, and its rules usually have been a template for stepped-up federal mandates.

It’s why all classes of EVs have been tried in California and where funding mechanisms are most in place to pay for it all, although other states like New York, Maryland, Massachusetts, Washington, Vermont, Colorado, Oregon, New Jersey, and Hawaii are surging in transportation electrification.

Some would say California is the “thought capital” of electrification.

The state also could be called the U.S. leader when it comes to incentives for commercial adoption of EVs and their technology like charging infrastructure.

See also: Pace of heavy EV sales quickens with two recent deals

The incentives there include the HVIP program—or the Hybrid and Zero-Emission Truck and Bus Voucher Project—which makes clean vehicles more affordable for fleets through point-of-purchase price reductions. HVIP is part of California Climate Investments, which puts billions of cap-and-trade dollars to work to help fleets purchase “clean” vehicles and break through their high incremental cost in the early market years. The HVIP project is funded by CARB through its Air Quality Improvement Program and Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund.

Other incentives include the California Energy Commission’s EnergIIZE Program, which is devoting $50 million for vehicles and infrastructure. And utilities in the state—Southern California Edison, Pacific Gas and Electric, Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, San Diego Gas and Electric—participate in dozens of EV and charging infrastructure rebate programs through the California Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Project (CALeVIP).

In just the latest of announcements about electrification in the state, a Volvo Trucks North America (VTNA) customer, WattEV, has ordered 50 Class 8 Volvo VNR Electric trucks to launch its Truck-as-a-Service (TaaS) model in California, the companies announced last month.

WattEV’s model provides shippers and carriers access to battery-electric trucks at a per-mile rate, including charging, that is on par with the total cost of operating diesel trucks, according to a release from Volvo. Over the next several months, the Volvo VNR Electrics will begin operating on routes between California’s San Joaquin Valley, Inland Empire, and the Ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles—all places where a lot of electric heavy-truck activity is centered.

Some of the California “thought leaders” came to the fore during a recent webinar, “Transitioning to a Truly Sustainable Fleet,” which was sponsored by the State of Sustainable Fleets (SSF) and stakeholders such as Penske, Daimler (maker of Freightliner’s eCascadia), fleet-management telematics provider Geotab, and electric utility DTE and organized by environmental consultant Gladstein, Neandross & Associates (GNA), to review work done by commercial fleets that have adopted sustainable vehicles of most kinds: natural gas, propane, hydrogen fuel-cell electric, and, yes, battery-electric vehicles (BEVs).

The webinar had as its baseline the findings of 2020 and 2021 reports by SSF on adoption of such vehicles and infrastructure. In the 2021 version of the report, 83% of early adopting fleets indicated they’d increase, rather than decrease, their use of clean vehicles, a sign that once funded and used, these vehicles can endure in the marketplace. Those fleets reported in 2021 superior TCO when using more mature clean tech such as compressed natural gas (CNG) in targeted “use cases” such as refuse, transit, and dedicated heavy-duty sectors. And according to that same report, BEVs are poised to become the leading clean fleet technology as soon as the next three to five years.

“The main thing is just understanding your fleet and your composition,” said Philip Saunders, who directs the City of Seattle’s Green Fleet Program and was a panelist during the webinar. Saunders said Seattle leans more and more heavily on electrification because the cost per kilowatt-hour for power there is only about 9 cents, which benefits TCO after the initial investment storm in vehicles and infrastructure blows over.

Seattle’s “green fleet action plan” calls for cutting its emissions in half by 2025 and to be emissions-free by 2030, Saunders said. That city has electrified 11% if its fleet of 4,100 vehicles using plug-in hybrids and is investigating hydrogen power. He said Seattle’s fleet phases in sustainable vehicles at year’s end, when “we have a roundup where vehicle replacement comes up, and that’s a time to evaluate more sustainable ‘green options.’”

Saunders suggested this as a strategy for any public or for-profit fleet.

Editor’s note: This is the first part of our look into the many aspects of EV adoption and the questions fleet operators should ask before making the leap to electrification. Part 2 and Part 3 will appear this week. These stories ran in abbreviated form as one piece in the April edition of FleetOwner magazine.

Source https://www.fleetowner.com/