Federal efforts are well underway to expedite the voluntary adoption of advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS) in trucking, particularly for Classes 7 and 8 vehicles. In the coming months, trucking’s federal regulatory arm, research groups, and industry associations will wrap up a year one assessment on how the metrics for motor carrier and driver acceptance of ADAS has changed, as well as how the industry is working to overcome some of the barriers that may still exist for some of these technologies.

Touted as potentially lifesaving systems, ADAS technologies fall into four categories: active braking systems, active steering systems, active warning systems, and camera monitoring systems.

See also: ADAS in trucking: How insurance companies, attorneys are using fleet data

The Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA) has teamed with the American Transportation Research Institute (ATRI), American Trucking Associations (ATA), ATA’s Technology & Maintenance Council (TMC), Owner-Operator Independent Drivers Association (OOIDA), Virginia Tech Transportation Institute (VTTI), and various suppliers on an initiative called Tech-Celerate Now. The overall intent of the program is to provide outreach materials for fleets to implement ADAS and training materials for drivers and maintenance personnel related to ADAS operation, inspection, maintenance, and troubleshooting.

VTTI has been studying heavy vehicle safety since around the year 2000 and has focused much of its research on commercial driver behavior as it relates to safety. Since safety technologies in trucking have become more prevalent and advanced, VTTI is now heavily focused on the vehicle technology side, explained Matt Camden, senior research associate for VTTI’s Center for Truck and Bus Safety. And ADAS has become one of VTTI’s main focal points.

VTTI uses data-collection equipment and sensory data to collect information on what the trucks are doing as drivers deliver freight. VTTI also collects crash and vehicle data from trucking companies to assess the impact of technology on a crash or a fleet’s overall safety performance.

One VTTI study used carrier-collected data to assess the safety benefits of ADAS technologies like lane-departure warning, roll stability control, and forward-collision warning to see if trucks with these systems were involved in fewer crashes. And they were, Camden noted.

“We followed up that study with other naturalistic driving studies,” Camden said. “We’ve looked at automatic emergency braking (AEB), and we know that the technologies work. The technology is working to prevent crashes that they’re supposed to help prevent, and it’s pretty much consistent across not just the research that we’re doing, but for all others who are doing research on heavy vehicles.”

See also: Trucking’s ADAS technologies still have many barriers to overcome

Over the course of a decade or more, ADAS technologies in the commercial trucking space have really begun to advance. Earlier generations of technologies had more limitations, Camden said. For example, the very first few generations of AEB would generate more false alerts. The technology might alert drivers that they were about to hit something when, in fact, the truck was just coming up toward a roadside sign or overpass.

“That presented a lot of barriers for drivers in terms of acceptance,” Camden explained. “Drivers would get annoyed with the technology, and they would try to disable it somehow or sabotage it, or not pay attention to it, which limited its effectiveness.”

Current generations of these technologies have advanced and no longer pester drivers with upcoming overpasses or roadside signs.

Lane-departure warning is another system where the technology is improving, Camden said. This is another area in which drivers have expressed frustrations, especially when they are going through work zones or down roads where the lane markings aren’t clearly depicted.

Data from ATRI shows that ADAS technologies are almost without question better understood and better appreciated by motor carriers than they are truck drivers, Dan Murray, ATRI’s SVP told FleetOwner.

The challenge that commercial carriers face there is with retention efforts or potentially exacerbating the truck driver shortage.

“The dilemma we have as an industry is if the truck drivers are hesitant or have concerns, one of the last things we are going to do is invest in technologies that might chase away drivers,” Murray said. “The motor carrier side of the equation is aggressively pursuing an enhanced investment [in ADAS]. They are seeking data and information, they are seeking out pricing, and they are working closely with the suppliers to figure out what repair and maintenance cost issues are going to be. But a lot of that hasn’t percolated all the way through to the truck drivers.”

ATRI has put together a year one assessment of ADAS in trucking and sent its findings to FMCSA in January. ATRI data from baseline to year one—about a 16-month period—is showing improvements in awareness, perception, and adoption, Murray pointed out.

“But when you’re coming from low numbers, it’s easy to have high percentages,” he added. “We are going to work really hard to make sure people understand that we are moving in a good direction. But, overall, the total number of these systems that are out on the road today are still relatively small.”

After FMCSA takes a deep dive into the report, Murray said the report will be made available to the public, likely sometime in late February or early March.

Spec’ing ADAS

ADAS technology is commonly available from several manufacturers that offer an array of capabilities and functionality. These systems—known under several trade names such as Bendix Wingman, Daimler Assurance, Volvo Active Driver Assist, ZF OnGuard, and more—require equipment owners and users to follow correct maintenance and repair procedures to ensure proper operation, according to TMC.

TMC is working on a recommended practice (RP)—still in draft form—that offers general guidelines for medium- and heavy-duty vehicle fleets selecting and specifying ADAS technologies. The RP presents a two-step process for carriers to follow: a fleet self-assessment evaluation and a technology evaluation matrix.

For the fleet self-assessment, TMC notes that a critical part of selecting and spec’ing ADAS is an evaluation of the fleet’s operating profile and identification of safety exposures (both actual and potential). “This is important in determining the areas where incorporation of an ADAS component or performance characteristic may have the greatest impact on reduction of frequency and severity of accidents or exposures to accident-causing factors,” TMC stated.

As for conducting a technology evaluation matrix, TMC recommends fleets compare their needs to the various available ADAS features and performance settings, cherry-picking those that will achieve the best results. TMC recommends that once a fleet has established its ADAS needs, carriers should actively engage OEMs and suppliers.

TMC provided some examples of how certain fleets might spec their vehicles with ADAS technologies:

- A fleet operating straight Class 8 trucks in a local pickup-and-delivery operation with little or no limited access highway driving may decide the key ADAS components to include are AEB, blind-spot warning, rear cross-traffic assist, and vulnerable road user detection.

- A fleet with a high percentage of rural road night driving and a history of off-road excursions may include adaptive speed control, lane-keeping assist, road departure warning, and adaptive headlamps.

- A fleet operating in a rainy/wet or snowy region may spec optional auto wipers to keep the ADAS camera’s (and driver’s) field of vision unobstructed without the need to constantly cycle the wiper control.

- A fleet with a high percentage of over-the-road driving with an accident causation history related to driver inattention may select a full suite of assistive—versus warning—ADAS features along with adaptive cruise control, camera rear vision, and driver-facing camera systems and warnings.

“These technologies are moving targets, constantly evolving and improving,” Robert Braswell, TMC’s executive director, told FleetOwner. “Processors and sensors are challenged by limitations in processing speed and functionality; each generation gets better. Software algorithms need to handle extremely complex problems of dynamic traffic situations; these are constantly being improved. And when GPS is not available to the truck, better mapping systems can fill the gap. Standardization of nomenclature and design can also help in thespecification and maintenance of ADAS.”

TMC is working on several RPs in this area under the Tech-Celerate Now program.

System upgrades

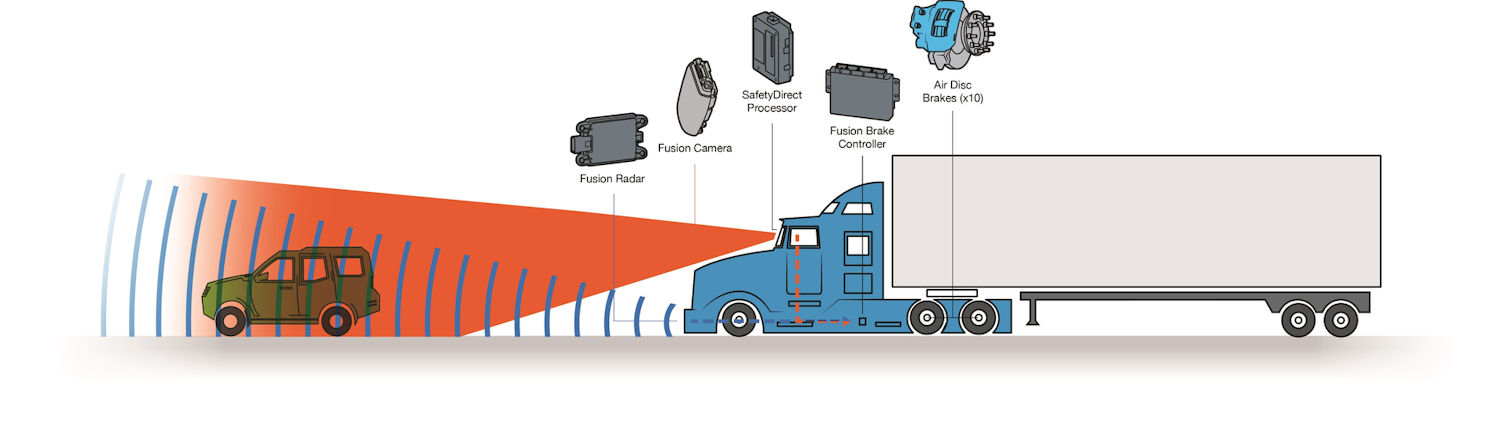

Historically, commercial vehicle safety systems have typically relied on an individual radar or camera to identify valid objects and vehicles before issuing an alert or taking action. Supplier Bendix Commercial Vehicle Systems has taken its latest driver assistance system, Bendix Wingman Fusion, a step further. Wingman Fusion integrates next-generation advanced safety technologies like radar, camera, and brakes into one system.

Bendix built Wingman Fusion from technologies including Bendix ESP Electronic Stability Program full-stability system, Bendix Wingman Advanced collision mitigation technology, and AutoVue Lane Departure Warning System from Bendix CVS.

New features for Wingman Fusion include stationary vehicle braking (SVB) and overspeed alert and action. With SVB, when a large, stationary, metallic object in a vehicle’s lane of travel is definitively identified as a licensed motor vehicle, the driver is notified up to 3.5 seconds before impact. If the driver doesn’t act, Wingman Fusion can automatically engage the brakes to assist in reducing the severity of or potentially avoiding a collision with the stationary vehicle. If the system cannot definitively identify the stationary object as a licensed motorized vehicle, the driver will get up to 3.0 seconds of alert to address the situation ahead; no automatic braking will be applied.

Overspeed alert and action uses Wingman Fusion’s camera to read most roadside speed limit signs. On the road, when traveling above 20 mph, the system compares the posted speed limit with the vehicle’s speed and provides two levels of alert and/or intervention to assist the driver.

For a level one intervention—initially set at more than 5 mph over the speed limit—the system provides an audible warning to the driver. If the vehicle is traveling at 10 mph or more over the speed limit–level two intervention—the system provides an alert and then a one-second dethrottle of the engine to get the driver’s attention.

T.J. Thomas, Bendix’s director of marketing and customer solutions—controls, advised that because there is a significant amount of engineering that goes into these upgrades, installing ADAS technologies is not a one-size-fits-all for fleets. Upgrades, he noted, are designed for the specific make, model, and year of the vehicle.

“We are noticing that the OEs are applying that technology a bit differently from make to make,” Thomas said. “A feature that might be called the same feature by Bendix might operate just a little bit differently given a different OEM. We would encourage the fleets to get their dealership involved to make sure they fully understand from that specific OE point of view exactly what feature set is on that vehicle they are ordering and to understand how the dealership or OEM describes it as well.”

Perceptions and driver acceptance

A potential barrier to overall adoption of ADAS technologies is getting fleets to understand the benefits of the systems as well as realistic versus unrealistic expectations of their performance.

“It’s easy to think that these systems would solve all crashes, but they certainly don’t,” Bendix’s Thomas pointed out. “They have limitations. The driver is always in control of the vehicle and is responsible for its safe operation.”

AEB, for example, is an extra pair of eyes and ears—but driving too fast or following too closely can negate the technology’s effectiveness.

“We say drivers should drive safe and astutely and if something happens fast that they might not notice, the systems are there to give them a helping hand,” Thomas added.

Driver acceptance and technician training also are key to making the most of ADAS technologies. Thomas stressed that both drivers and technicians need thorough training on the system and its limitations.

“If that is covered with the driver and the technician before the vehicle is put into service, then a significant number of questions are answered,” Thomas said.

“If you’re a fleet that is just coming up to speed or your technicians are still ironing out details on how they incorporate that into your fleet, that could be a barrier,” he added. “Many dealerships have a lot of training and are up to speed, but a fleet may or may not depending on how they maintain their vehicles.”

VTTI conducted a study about five years ago where researchers spoke with drivers about their experiences with the technology. By and large, according to Camden, most of the drivers who participated in that study said they didn’t like the idea of the safety technology at first. But once they experienced the technology working to prevent a crash, they began to buy in.

“They accepted it, they realized its importance, and they were able to tolerate some of these false alerts or situations where the technology could have performed a little bit better,” VTTI’s Camden noted. “Getting that experience is really big for the drivers in terms of acceptance.”

For Camden, a solution to help accelerate adoption and to overcome driver resistance is changing how the industry talks about ADAS. A lot of times, he said, drivers think that the technologies are taking over for them, or that these technologies are on the verge of replacing them.

“But really, that’s not what these technologies are doing,” Camden advised. “That’s not how they’re intended to work. They are intended to be a backup to the driver. Tractor-trailer drivers are professional, and the vast majority of them are really great at their jobs. The ADAS technology is there as their backup, and that one case when they may be looking in the wrong place at the wrong time.”

ATRI’s Murray also pointed out when it comes down to driver acceptance, employee drivers have higher awareness and positive perception of ADAS technologies than owner-operators. That’s because employee drivers are usually handed a truck with these systems already installed, while an owner-operator has to pay for specific technologies out of pocket.

Murray explained this assessment helps ATRI understand where more education and research are needed, particularly if there is another phase to the current research.

“One of the most interesting findings that has come out of both the year one and the baseline survey is that one of the top three preferred technologies both by motor carriers and drivers are road-facing cameras,” Murray noted. “What’s interesting about road-facing cameras is they are not an active safety technology in the classic sense. They are used by some motor carriers in terms of driver training if they see egregious behavior. It is a safety system in that regard, but in many instances, it is essentially a driving awareness tool.”

Driver-facing cameras, however, are a different story. These systems represent one of the top two least preferred technologies by truck drivers, according to ATRI.

“As long as the truck drivers dislike them, motor carriers are going to be very hesitant to incorporate [driver-facing cameras] because you don’t want an unhappy driver in the cab of your truck,” Murray said.

One side note to driver-facing camera systems, Murray added, is that fleets typically capture only 30 seconds before and after a safety-critical event, hard braking, crash, etc. A few carriers run them 24/7 for training purposes, but they are not capturing 24/7.

“That’s another one of those insights that drivers are not aware of,” Murray said. “The messaging has to be this is to prevent unintended consequences coming out of crashes and safety events.”

Alternatively, AEB is well-received by motor carriers, but there is a lot of concern among truck drivers that these systems will take over the driving activities.

“We need to get more drivers in vehicles that have these systems, possibly even driving simulators that use these systems,” Murray explained. “But at the very least, we need to put together case studies and testimonials from drivers who use them and like them and share those with truck drivers who are unaware and have hesitancies.”

As to whether FMCSA will eventually regulate ADAS industrywide, Murray believes that for the technologies that make sense, it will be an evolution.

“I think everyone is moving toward active safety systems and away from warning systems,” Murray said. “Regulatory agencies are going to probably cherry-pick those that make the most sense for regulatory consideration.”

Murray pointed to when roll stability and electronic stability control were first mandated in the earlier 2000s.

“By the time it was mandated, those systems were standard on the large majority of trucks out there, and the drivers and carriers had no issues,” Murray explained. “I think that’s a decent analogy for some of these promising systems. We will move quickly on the industry side to adopt when they are proven, and regulatory actions will follow that increased adoption level.”

Source https://www.fleetowner.com/