Deconstructing the events following a Mid-Atlantic fleet’s truck crash shows nuclear verdicts are avoidable with the proper equipment and technology.

Four years ago, John Vaccaro, president of the New Jersey-based Bettaway Beverage Distributors Inc., picked up the phone and got the news every fleet owner fears: One of his drivers was involved in an out-of-state accident involving multiple vehicles and serious injuries. Someone also required a medical evacuation.

Vaccaro said shocks rolled through his body as more calls with more chilling details crept in. He contemplated how this could happen and if some decision he made caused this tragedy. Thoughts also jumped to how this could impact the future of the business his father entrusted to him in 1999, and all those 250-plus employees depending on it.

“I just knew that this was the one,” Vaccaro told FleetOwner, referring to how this tragic event, in which one person was left permanently injured, would also forever alter the company. Bettaway, which started as a soda factory, now in its 38th year, also includes a supply chain and logistics division, and pallet service.

While just one of 121,000 large trucks and buses were involved in an injury crash in 2017, according to Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA) data, the incident that tested Bettaway’s operational character represents the full scope of what a fleet faces when a crash like this occurs.

Better safe than sorry

One outcome of the crash was that it would ensure Bettaway doubled down on its deployment of safety technology, such as advanced driver assistance systems for its fleet of 150 tractors and 750 trailers.

“We accelerated trade-outs of existing Freightliners that we had to bring our fleet up to almost 95% collision avoidance,” Vaccaro noted. The fleet’s newer Cascadias employ various versions of the Detroit Assurance safety system.

Because of leasing terms with Penske and Ryder, among others, the process took about 12 to 18 months.

“How could you not choose to have collision avoidance on a truck,” Vaccaro pointed out. “Whatever the expense, it was irrelevant. If you avoided one crash or one injury, it would be worth it.”

And Vaccaro knew from operating in the metropolitan New York area that collision avoidance technology was worth the investment.

“We’re in a business that this could happen every day,” he said. “The more trucks that we run in a densely populated area, the odds are against us that this will happen again.”

At the time of the crash, Vaccaro, who had already prided his fleet as always having “the latest and greatest” equipment, had trucks spec’d with Wabco’s OnGuard collision mitigation system with active braking. That technology advancement launched in 2014 and within a few years, one-third of Bettaway’s power units had the radar-based solution. Unfortunately, the truck involved in that 2017 crash was a model year 2013 Freightliner, so it did not have collision avoidance.

“We don’t know what happened, but for sure the collision avoidance would have helped,” Vaccaro asserted.

Bettaway’s fleet of 150 Freightliner Cascadias are equipped with collision avoidance to prevent crashes, and dash cams to understand how crashes happened.Photo: Bettaway Beverage Distributors Inc.

The addition of dash cameras has helped Bettaway understand what happens on the road. This has already paid dividends with “a rapid decline in claims,” Vaccaro said. In one instance earlier this year, a refuse truck going in reverse in a parking lot smashed into the hood of a parked Bettaway Cascadia, leaving the new truck with $25,000 of damage. Without the video, the location of the damage would indicate to the insurer that the Cascadia drove into something.

The video is also used for training drivers and rewarding good behavior.

The nuclear option

While Bettaway becoming safer is the bright side to this tale, there’s a darker underbelly as well. As much faith as Vaccaro has in modern trucking technology, he has perhaps even more disdain for the American civil justice system.

“The system is broken; it makes me angry,” he said.

It wasn’t always that way. Even the night of that 2017 crash.

“I remember going home and thinking, ‘We did everything right,’” Vaccaro recalled.

Along with the fleet’s due diligence toward safety, the Bettaway driver and the truck were not found to be at fault during the accident, according to Vaccaro. He added that the truck, driver, and company were all in full DOT compliance with hours of service and the equipment was found to be without defect.

“There’s nothing that should point to anything wrong nor was anything found,” Vaccaro said. “Because of the nature of the accident, we knew we were up against something big.”

Bettaway had planned for “the big one,” though, carrying umbrella insurance liability coverage of $5 million, nearly seven times more than the legally mandated minimum of $750,000. The fleet’s trucks had been involved in accidents before, but none above $400,000, Vaccaro maintained.

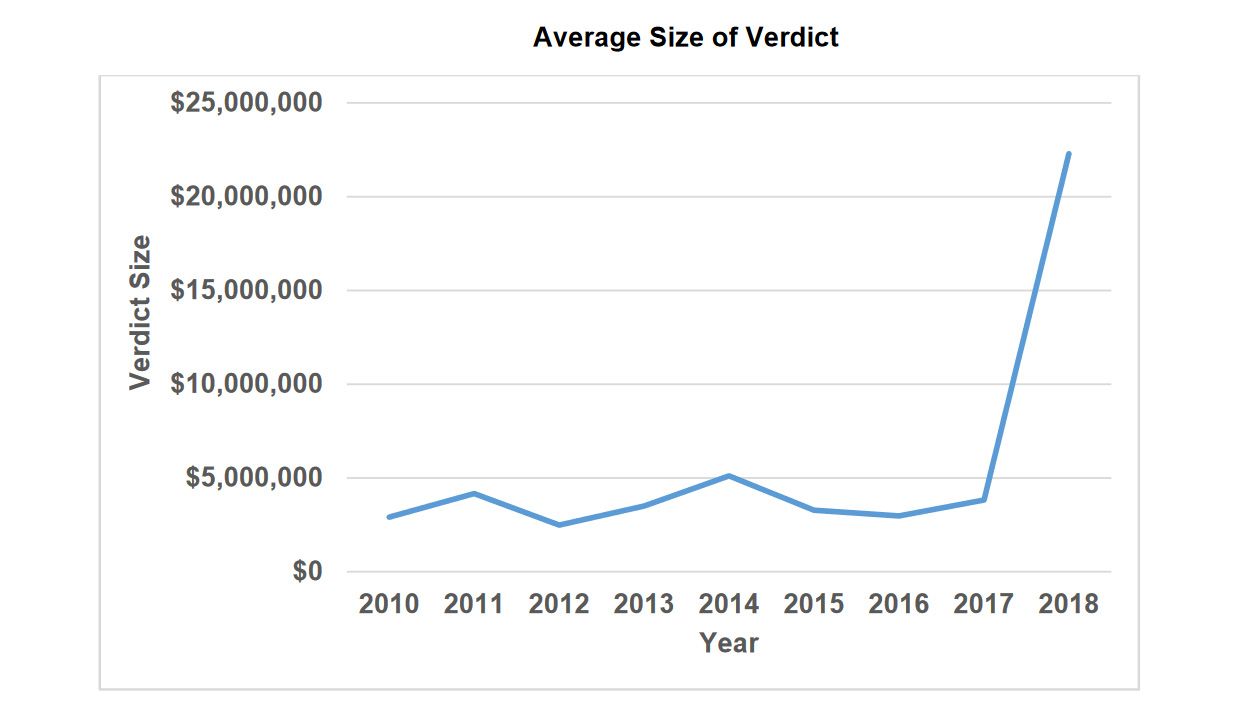

There was still reason to worry, as nuclear verdicts, or those in excess of $10 million, were on the rise. From 2017 to 2018, the threat of nuclear verdicts reached a new crescendo, according to the American Transportation Research Institute (ATRI), with the average verdict award growing 483% year over year.

Notably in 2018, a $90 million verdict was levied against Werner Enterprises in Texas’ Harris County. That stemmed from a 2014 crash that killed a 7-year-old boy, left his 12-year-old sister with brain damage, and injured another brother and their mother. The pickup carrying the family had lost control in icy conditions, crossed the Interstate 20 median, and oriented itself going with traffic just before the Werner truck, operated by a student driver, made impact with the pickup’s bedside. Officers at the scene did not cite the Werner driver, but the jury found that Werner was liable, as it was an unsupervised student driver delivering a just-in-time load to California.

“There was really no thought prior to that [Texas ruling] that something like that was even possible,” Vaccaro said.

In the current litigious landscape, such things are becoming not just possible but probable. When the Bettaway case was being brought to civil court in 2020, the company found itself in the python-like grip of the plaintiff’s lawyer.

The specific details must remain between the two parties, but Vaccaro, who prefers “to fly under the radar,” felt the essence of what was said should be brought to light. In no uncertain terms, this plaintiff’s lawyer made it clear he thought Bettaway was a decent business with plenty of assets, from which this particular lawyer wanted to squeeze every last dollar.

And to do it, he would likely employ the reptile theory to sway the jury.

Cold-blooded case

“As human beings, we all have this reptilian brain, meaning we all have this innate need to feel safe and secure in our world and our communities,” explained Rachel York Colangelo, national managing director of jury consulting for Magna Legal Services. The end-to-end legal service provider helps the defense team for trucking companies choose the 12 people who will decide how much is awarded to the plaintiff side in an accident if a case goes to trial.

Colangelo said the objective of a plaintiff’s lawyer is “inciting fear in the hearts and minds of these jurors,” that if these trucking companies aren’t taught a lesson, the next truck-related crash could involve someone in that jury. “That is directly related to these huge nuclear verdicts,” she said.

Juries aren’t able to enforce specific fleet safety changes, so their only recourse is targeting their bank accounts, Colangelo reasoned.

“You’re taking the focus away from this particular plaintiff and what happened in this incident, and what their damages are, what their compensation should be, and shifting that focus around to the conduct of the defendant, making this a statement about the trucking industry’s policies and whether they’re adequately prioritizing safety,” she explained.

“That fear, and attention on the defendants, quickly turns to anger, and an angry jury becomes punitive,” Colangelo added. For this reason, she said engineers, who “carefully think through everything, make great jurors.”

The best defense against such torts, often punitive actions toward fleets that disregarded or neglected safety, is being a responsible fleet that invested in safety technology.

“Good fleets are being proactive, thinking ahead to establishing good quality policies that do put safety first, and following through on those policies,” Colangelo said.

A fleet’s safety manual tells a lot about the company culture, and one lacking in information or that contains unclear wording could damage a defense. Texas defense attorney Glenn J. Fahl, who has taken 19 commercial vehicle cases to court, said fleets should do a “litigation drilldown” of their manuals, so in the event of an accident, it won’t give the jury reason to doubt a fleet’s attention to safety.

“Revise it now, not after being tortured in a deposition on a bad case,” he said.

If the problem is emotion, the solution should be knowledge. That means if a trucking company representative takes the stand for the defense, they need to know the safety policies inside and out and be able to defend them.

“I’ve seen this witness testimony from the company sort of blow a case up, whether that’s in a deposition or at trial, because a corporate representative is uninformed,” Colangelo said.

Fortunately for Bettaway, they never had to face a jury, as Vaccaro called for a “Hail Mary pass” on the day of jury selection and demanded a court-appointed mediation.

“I wanted a fair shot under the right light, and I wanted everyone to know that we cared, and we wanted to take care of this,” Vaccaro said.

The terms were undisclosed, but Vaccaro thought it was better than the alternative: “Nothing good was going to come from going to jury.”

Blood letting

The potential for big pay days has led to “more blood in the water,” Vaccaro said, illustrated on billboards advertising plaintiff’s lawyers, lurking above urban highway stretches like sharks. And each headline-making jury award is like a truckload of chum. “The more that takes place, the more that’s going to engage the entrepreneurialism in attorneys.”

This has not gone unnoticed by trucking’s leaders. In 2019, Chris Spear, president and CEO of the American Trucking Associations, had publicly stated “nuclear verdicts are strangling our industry.” It has also got the FMCSA mulling a minimum insurance of $2 million. The premium increase would make it harder for fleet drivers to branch out on their own, a reason the Owner-Operator Independent Drivers Association (OOIDA) has been a staunch detractor of the idea, and a reason the group could not support a Democrat-led infrastructure bill last summer.

In a letter sent Feb. 1, a coalition of more than 30 organizations, including OOIDA, sent a letter to the House Committee on Transportation & Infrastructure that read: “An increase in insurance requirements is wholly unnecessary, would do nothing to improve highway safety and would have a severe negative impact on truckers, farmers, and manufacturers by significantly increasing their operational costs.”

The letter went on to say this would lead to more American job losses, all for the 0.6% of commercial motor vehicle crashes that the exceed $750,000.

There is a fine line. For example, an Army veteran in Florida who tried to avoid a 45-car pileup swerved his motorcycle into the emergency lane and hit a stopped truck. He sustained severe injuries, including a shattered pelvis, and after six months in the hospital, must carry a colostomy bag and endure constant pain. The medical bills alone were nearly $750,000.

In an October 2020 virtual hearing held on Zoom, a jury valued the injured man’s suffering at $411 million, which would be paid out by an owner-operator whose speeding, and a subsequent jackknife in the rainy conditions, they reasoned, caused the accident and the plaintiff’s traumatic transformation. The single-driver company has lost its authority and is unlikely to have the means to pay off the exorbitant fee.

Vaccaro understands both sides, though not the imbalance.

“When someone’s injured, they should be compensated without a doubt,” he said. “But the numbers don’t make sense.”

If a case does go to court, there are two ways to mitigate the damage, Fahl said agreeing to a high-low settlement, where a payout would not exceed a certain number if the defense loses badly nor go below it even if the defense’s argument is airtight.

“It may be a hard one to choke on if you [beat] them, but it’s still better than $100 million,” Fahl said.

Another option is to have an appellate council sit in, “so that if all of these erroneous rulings occur, you can then appeal and get it reversed.” Fahl noted from personal experience that the judge in the Werner case let the plaintiff’s side submit “anything into evidence.” The appellate council is more discerning. “They actually know the law,” Fahl said.

The best solution, in Vaccaro’s opinion, is to cap the award amount of verdicts through tort reform. If not reined in, his concern is that the bar of entry for owner-operators and smaller trucking companies will be too high due to higher premiums: “The whole supply and demand and free market model is going to be out of kilter if it is not hauled in,” he said.

He expects the fallout from nuclear verdicts to continue unabated though.

“I have no confidence that anything like that would occur, because of the amount of money that’s involved. What attorney or what lobbyist is going vote to shut that down?” Vaccaro asked.

Until sweeping changes are enacted, the fleets and drivers labeled heroes throughout the pandemic must prepare to someday become pariahs before a jury of their peers.

“We were good, law-abiding operators with good equipment and over-insured, in my mind,” he said. “Why should we as a company face peril?”

By John Hitch

CUT COTS OF THE FLEET WITH OUR AUDIT PROGRAM

The audit is a key tool to know the overall status and provide the analysis, the assessment, the advice, the suggestions and the actions to take in order to cut costs and increase the efficiency and efficacy of the fleet. We propose the following fleet management audit.