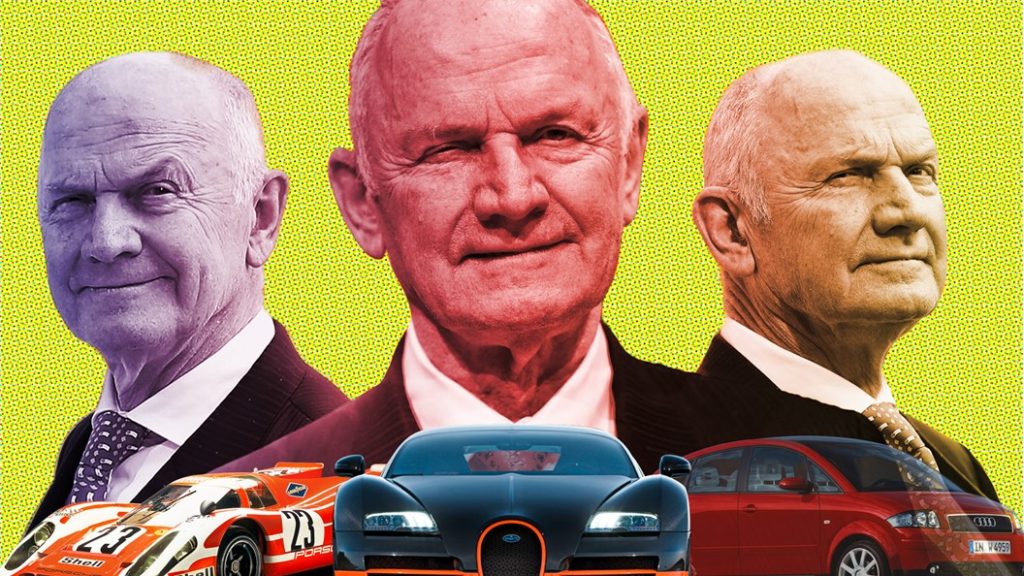

Engineering visionary, monosyllabic master tactician, Porsche patriarch, billionaire: no car boss has innovated as ruthlessly as Ferdinand Piëch, the ex-VW chairman who died at the weekend.

Here we’ve put together two articles that get closer to the an architect of the VW group as we know it. First, an in-depth interview from our European editor Georg Kacher, and next a brief look at some of Piëch’s most important moments.

Keep reading for our tribute to the grandson of Ferdinand Porsche, a titan of the German car industry – and look back at his greatest achievements and the legacy he leaves behind.

Piëch and me: an interview by Georg Kacher

It was the same routine every night. Aperol Spritz in hand, I looked across the bay from the balcony of our Woerthersee hotel to the Piëch property, wondering whether He was there, picturing the line up of secret prototypes and exotic cars, prioritising in my mind the many subjects we could have talked about, right there and then. Though I drove past many times, sadly I never breached the vast lakefront estate, protected by an impossibly tall green wrought iron fence straddled by surveillance cameras. So close and yet so far. Which describes my very distant relationship with the éminence grise who has pushed the car industry faster and further forward than any other engineer, strategist or investor.

Were your university days productive? That’s when Ferdinand Karl Piëch conceived his first Formula 1 engine, before joining Porsche in 1963 aged 26. He quickly moved up through the ranks, but in 1972 the families decided that all members of the Piëch and Porsche clans had to resign from leading managerial positions. Piëch founded his own Stuttgart engineering bureau and developed a five-cylinder diesel engine for Mercedes before moving on to two pioneering decades at Audi.

I had met Piëch on a couple of launches, but it quickly transpired that he was not exactly keen on talking to me, let alone to answer questions. A typical riposte to a complex, tech-heavy opening gambit was a long silence followed by a broad grin and a monosyllabic ‘yes’ or ‘no’. Was there something wrong with my communication skills? ‘Piëch is a secretive person,’ said of one many PR persons who had the good or bad fortune of serving The Big Boss. ‘He may tell you things, but only on his own terms and conditions. And he hates somebody stealing his thunder. You always do this with those future product stories he cannot control.’

When CAR ran a piece titled Quattro King on Thomas Ammerschläger, Piëch was reportedly furious because he felt that neither he nor the team leader Jörg Bensinger were given sufficient credit for the breakthrough four-wheel-drive car. The old man (as his own team members started calling him when he was still relatively young) tended to take criticism personally, and there was plenty of negative press when Audi shed its grandpa image and accelerated aggressively into the quattro era.

All of this was of course part of Piëch’s grand scheme of Vorsprung durch Technik: the aero design, the first foray into lightweight construction, the brand-shaping motorsport activities including the World Rally Championship. Under FKP, the motorsport division even developed a mid-engined group B racer which was mothballed at the eleventh hour, there were plans to revive the legendary Horch brand with a high-end luxury saloon loosely based on the first Audi V8 (think Mercedes and Maybach), and motorcycles were also on the man’s wish-list long before the acquisition of Ducati this year.

After turning around Audi, Piëch was in 1993 appointed the new number one trouble-shooter at Volkswagen where he replaced Carl Hahn. He inherited a pretty unsuccessful model range but, within five years, the ailing brand introduced the entry-level Lupo, the New Beetle, the Golf IV with its game-changing quality, a new Bora and Passat, and the Sharan co-developed with Ford.

In an attempt to cut costs, Piëch hired GM’s purchasing czar José Ignacio Lopez and seven members of his team, among them the current procurement chief Francisco Javier Garcia Sanz. It was a damaging deal: under Lopez, truckloads of Opel documents were reportedly hauled from Rüsselsheim to Wolfsburg, VW adopted GM’s just-in-time production concept and farmed out an increasing portion of the R&D work to the supply industry. The ivory tower collapsed big-time. Lopez was forced to step down, VW had to pay a penalty and buy $1bn worth of GM parts as compensation, and the underfinanced and overstressed suppliers created what Piëch hates most – a glut of quality problems which took years to fix.

Senor Lopez paid the penalty, like many Piëch executives. No fewer than three Audi chiefs bit the bullets fired from FKP’s pistol: Franz-Josef Kortüm was dismissed after only 13 months, Herbert Demel was expelled to Brazil, Franz-Josef Paefgen was sidelined to Bentley one day before his expected board nomination. Bernd Pischetsrieder received a new, five-year contract only to be dethroned a few months later, along with his deputy Wolfgang Bernhard. Porsche’s Wendelin Wiedeking fell over his ill-timed and in retrospect ill-advised VW takeover bid; Karl-Thomas Neumann was downgraded from VW China chief and potential group boss.

Ferdinand P talks and acts like no other captain of the industry. He selects his words carefully, is softly spoken even when his eyes are on fire, has a low and occasionally piercing voice with a faint Austrian twang that sounds cynical at best and snide at worst. A professed dyslexic, he understandably struggles with speeches but it’s always interesting to listen in when he has something important to say.

These thinly veiled programmatic statements tend to be issued at motor shows or car launches. I still remember remarks like ‘things at Audi are static’ which did not bode well for Demel, that Wiedeking ‘still has my full confidence’ which marked the beginning of the end, and ‘some understand this business better than others’ which was another way of saying goodbye to Bernd Pischetsrieder.

I filed about five interview requests over the past 40 years, but I got nowhere. The answer was always the same: he doesn’t want to. I even approached Uschi Piëch, his wife and the mother of three of the twelve children he admits to – although Piëch keeps pointing out that 13 is his lucky number. At the Geneva show one year, I asked the first lady to cook him apricot dumplings after my grandma’s irresistible receipe. Six months later, Piëch quipped: ‘Wrong approach. I would have preferred roast pork.’ FKP definitely has a sense of humour. But some of us must dig long and hard to access it.

We had a few fallouts over the years. At the Audi coupe’s launch in 1988, Piëch asked me what I thought of the car and I said ‘not much: oddball hatchback design, no high-performance version, uninvolving drive’. He listened, nodded and left me standing. Prior to the launch of the Golf IV in 1997, my German publishers ran an accurate scoop of the new model which infuriated Piëch. He cornered me and hissed: ‘Know how much your stories are costing us?’ ‘No,’ I said, ‘but why don’t we sit down to discuss it?’ He was not amused.

Occasionally, I felt quite close to The Man. One of the most memorable moments was driving one of his pet projects, VW’s Phaeton, in Dubai. In the morning was a dynamics test where the heavy saloon understeered like a truffle pig and handled with the ponderousness of the Costa Concordia. Critical comments were voiced, and the climate turned frosty despite the heat.

After lunch, GK and photographer Jürgen Skarwan headed for the designated test car to commence our drive through the desert – only to find Uschi Piëch already installed in the passenger seat and Ferdi (only close friends are allowed to call him that) strapped in behind his wife. The posted speed limit on the freeway was 120kph, but Piëch kept pushing for more. At an indicated 250kph, I backed off – partly because we set off automatic radar traps complete with flashguns almost every 5km. Said the chairman with that eerily casual tone of voice: ‘Don’t worry. The speeding fines are already paid for. And if you put your foot down hard enough, the car will do 280kph. This particular model is not governed.’ Smiling and chatting and totally unperturbed by the climbing speedometer needle, Mrs Piëch kept taking pictures she promised to send but never did.

Ferdinand Piëch is not only a gifted engineer and one of the few true visionaries of the trade, he also is a highly competent driver. After dinner at the ur-quattro’s launch in Garmisch in 1980, he decided to demonstrate the benefits of four-wheel drive on the snow-covered Fernpass. I tried to follow but lost sight of his tail-lights after a dozen corners.

Piëch and current VW boss Martin ‘Wiko’ Winterkorn still attempt to test drive all new models from all brands in all conditions. Every year, management attends a collective summer drive in Africa and a winter drive in Scandinavia, Canada or Russia. ‘Where exactly are you going?’ I once asked Piëch, not really expecting detailed GPS info. For a change, he answered like a shot. ‘In summer, the preferred destination is a secret African oasis in the middle of nowhere.’ Then he smiled and added: ‘In winter, we go to a place where they first shoot and ask questions later.’

There are many legends and myths surrounding the steep career of ‘cutline Ferdi’, so named because the certified engineer is obsessed with ultra-narrow panel gaps, a surefire indication of excellent structural rigidity and top-notch build quality. Another real forte is his amazing eye for design. Piëch attends most product strategy design meetings where all marques display their latest work, frequently hosted by Seat in Martorell where the light is particularly favourable.

Together with his pal Wiko, design chief Walter de’Silva and Hubert Waltl – a seasoned bodywork specialist – he will go through the exhibits one by one, instructing changes here and there or giving the thumbs down, as he recently did to Bugatti’s Galibier limo and the Bentley 9F SUV. Piëch is both feared and admired for his meticulous attention to detail, for his ability to assess and adjust every line and curvature, and for his constructive criticism which is voiced irrespective of rank and position. ‘Everyone can make a mistake,’ is one of his sayings. ‘What I don’t tolerate is someone making the same mistake twice.’

Piëch’s garage reportedly features a wide variety of cars, including one of the first Veyrons and a more recent Supersport, an R8 coupe and Spyder, a Cadillac Escalade, a Ferrari 458 and of course a Ducati motorbike, to name only a small selection. No, there is no 911, but an original Porsche Bergspyder, one of FP’s early works. Piëch still feels particularly close to Audi, but it’s not just Ingolstadt which sends pre-production cars to his residences for early appraisal: Bentley, Seat, Lamborghini, Skoda and Volkswagen all follow suit. And rumour has it that all the vehicles can be opened, locked and started with the same master key.

When a car is built for the personal use of the chairman of the supervisory board, it will likely be painted black and clad in magnolia leather, his favourite colour and trim combination. Occasionally, Piëch voices special requests, like a 500bhp Golf 4Motion dressed up like a standard Golf R, or a couple of innocent looking Skodas equipped with highly tuned VW engines. The Man likes coupés, but he dislikes convertibles.

Even though the Porsche and Piëch families control 90% of the Porsche Holding company which in turns owns 50.7% of Volkswagen, the grandmaster of the VW empire is not what you would describe as big spender. True, he did commission a bespoke yacht that has yet to sail the seven seas, and he does have a soft spot for fast machines on two and four wheels.

But the trademark pinstripe suits are not made to measure in Naples where other VW bigwigs shop, the black Trickers shoes are bought in bulk in London, the favourite watch is a relatively inconspicuous steel Breitling with a blue face, the scuffed leather briefcase harbours a whole batallion of black Montblanc pens. Although Piëch is a big fan of fine craftsmanship, he prefers understated proportions and clever details like the Phaeton’s draught-free air conditioning to overt opulence. No, the Phaeton has not been a commercial success, but Piëch will persist with it.

True, Piëch has not yet turned around Seat, that loss-making legacy from way back when. He has not taken the strategic lead in terms of electromobility, hybridisation and fuel-cell technology. He has failed to acquire Alfa Romeo. He was not able to fix VW’s rift with Suzuki. But with this man, absolutely nothing is final. Does he still harbour hopes of acquiring Alfa Romeo, or see potential in Proton, or Opel? And how might he steer Porsche under the VW umbrella? Plenty of topics to discuss. Many riddles to be solved. But how to unearth an approach that opens those green metal gates. ‘Waiter, another Aperol Spritz!’ Next year, we’re going somewhere else for our summer vacation. I am conceding defeat.

Piëch’s greatest acheivements

1. Porsche 917

This kick-started the Porsche racing legend, and elevated Porsche into the top-tier sports car pantheon, alongside Ferrari. Masterminded by Piëch, the 917 was probably the most iconic sports racer of all time. After it stopped winning Le Mans, an open-top turbo version, the 917/30, dominated the Can-Am series.

2. Audi Quattro

Before Quattro, Audi was a name plate with no kudos, a maker of tinselled VWs. New boss Piëch knew that ‘statement’ cars were crucial, and there have been few statements bolder than the Quattro. It won rallies, pioneered all-wheel-drive sports cars and elevated Audi into the BMW and Mercedes league.

3. Bugatti Veyron

As an engineer, Piëch pushes boundaries. ‘Impossible’ is a challenge, not a barrier. Why not engineer a 250mph supercar? Detractors say Piëch has had too many such unprofitable vanity projects. Yet such dreams spur progress and build brands better than any marketing campaign.

4. Platform sharing

We had platform sharing well before Piëch, from the Japanese, Americans and even VW – remember the Beetle-based Karmann Ghia? But VW under Piëch took the concept to a new level, slashing development costs and revolutionising the car industry.

5. Volkswagen XL1

Another Piëch ‘vanity project’. Who else would think to sell a two-seat microcar for £98,000? That’s the price of progress. Just as the Veyron proved a production car could do 250mph-plus, so the XL1 proved a car sold to the public could achieve fuel economy of one litre per 100km, or 280mpg.

6. Saving Volkswagen

When Piëch became CEO in 1993, Volkswagen was nearly bankrupt. When he stepped down as chairman in 2015, Volkswagen was a global automotive powerhouse of eight car brands, on the brink of becoming the world’s top-selling auto maker. Mind you, VW without Piëch felt a bit like Apple without Steve Jobs. It still does, really.

7. Audi A2

Another magnificent loss leader, the A2 may well be the most intelligently engineered small car of the past 20 years. It was light, aerodynamic, spacious and made of aluminium. Pity the A1 and A3 that followed were steps backwards.

8. Dual-clutch transmissions

A few makers had been experimenting with this for years. Porsche and Audi first made it successful, winning in motorsport. Volkswagen was first to put it on sale. Now widespread, it gives better performance and smoothness than a normal manual, and better efficiency than a torque converter auto.

9. A thriving Lamborghini

Lamborghini has always danced close to the red zone. Neither founder Ferruccio Lamborghini, nor Chrysler or Malaysian investors could make any money. Now under the ownership of Volkswagen, it’s a strong, Ferrari-rivalling business. Plus the cars, while still exhilarating to drive and thrilling to view, are now built like Audis, not kit cars.

10. Dodging Dieselgate

Piëch cleverly schemed to hold on to power at VW for decades. Rumours persist that he may have masterminded his own departure in 2015, a few months before the VW Dieselgate scandal broke, leaving CEO Martin Winterkorn holding the bag. We wouldn’t put such wily tactics past this arch strategist. It’s typical of Piëch’s ruthless focus that Wolfsburg has seemingly bounced back from the emissions cheat device scandal relatively unscathed, as it’s pivoted around the drive to electrify its range.

CUT COTS OF THE FLEET WITH OUR AUDIT PROGRAM

The audit is a key tool to know the overall status and provide the analysis, the assessment, the advice, the suggestions and the actions to take in order to cut costs and increase the efficiency and efficacy of the fleet. We propose the following fleet management audit.